On this edition of Your Call, listen to a conversation we recorded live at Mission High School as part of our series HEAR: Histories of Exclusion and Resistance.

Hear from Chizu Omori, a Japanese American writer and activist who was forced into a World War II camp at 12 years old, and Gilda Temaj Marroqin, a college student who traveled alone to the US from Guatemala at age 16 and was briefly detained by US officials. What are the lasting impacts of holding children in internment camps and detention centers?

Guests:

Chizu Omori, writer, activist and WWII internment camp survivor

Gilda Temaj Marroqin, Ethnic Studies student at UC Berkeley

Web Resources:

Then They Came for Me: Who is an American? (Event link)

KQED: 'It's Horrifying': 11 Bay Area Artists Speak Out on Child Detainment at the Border

Indybay: Day of Remembrance: Japanese Americans Recall WWII Incarceration

Transcript

Rose Aguilar: Welcome, I'm Rose Aguilar and this is a special live taping of Your Call, recorded at Mission High School in San Francisco. Today's show is part of a series of events our team is producing called HEAR: Histories of Exclusion and Resistance. In this series, we are exploring the connections between the forced removal and imprisonment of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans during World War II and modern policies that threaten civil liberties.

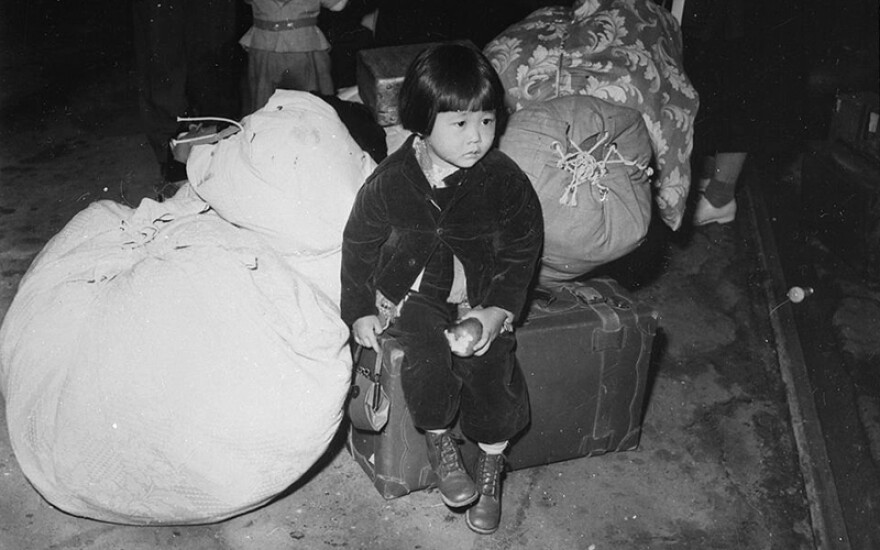

In early February 1942, the War Department, which is now called the Department of Defense created 12 restricted zones along the Pacific Coast and established curfews for Japanese-Americans, enforced under threat of immediate arrest. Later that month came Executive Order 9066, which gave the U.S. military authority to exclude any persons from designated areas and paved the way for forced relocation and incarceration. The Army oversaw the forced relocation of thousands of families who had just days to dispose of anything they could not carry with them. Anyone who was at least 1/16th Japanese was ordered to leave, including an estimated 17,000 children under 10 years old.

Today, thousands of children from Central America are detained in camps and so-called shelters around the United States on the orders of the U.S. government and its Border Patrol and Immigration Enforcement system. According to CBS, U.S. immigration authorities apprehended or turned back more than 100,000 migrants including approximately 53,000 families and nearly 9,000 unaccompanied children along the U.S./Mexico border. Just last month more than 2,600 children were separated from their families by U.S. officials. Many of the parents have been deported without their children and they have no idea when or if they will be reunited.

So today we're going to talk about the xenophobia and the hysteria that enables the imprisonment of families and children. We will also talk about the experience of incarceration and what happens afterward and the long-term impacts.

And today we are joined by two guests. Chizu Omori is a writer and activist based in Oakland. When she was 12, she and her family were forced from their home in Southern California to a Japanese internment camp in Arizona in 1942. Chizu is part of the Nikkei Resisters. That's a group of Bay Area Japanese Americans who use the legacy of Japanese internment to show that civil liberties can be taken away at any moment. They also join in solidarity with oppressed people. Chizu and her sister Emiko, who is also here today, made Rabbit in the Moon. It's a documentary that tells a complex and intimate story of the internment camps.

And if you're located in the Bay Area, Chizu is taking part in an all-day event called “Who is an American?” It is Saturday, May 11th from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. at the Presidio in San Francisco, 100 Montgomery Street, and we’ll put information about this on our website yourcallradio.org. Chizu, thank you so much for coming.

Chizu Omori: I'm glad to be here.

RA: We are also joined today by Gilda Temaj Marroqin, a student in the Ethnic Studies program at UC Berkeley. Gilda came to the United States from Guatemala on her own when she was 16 years old – that was six years ago. Gilda was briefly detained in two different facilities before she was able to move to San Francisco and she's now living in the East Bay. Hi Gilda, thank you so much for joining us.

Gilda Temaj Marroqin: Thanks for having me as well.

From the 1940s Crystal City Internment Camp to today’s South Texas Family Residential Center

RA: Chizu, you just recently went to a pilgrimage and a protest at what was formerly the Crystal City prison camp where 4,000 Japanese Americans were held during World War II and just 40 miles from that prison camp, there's now the South Texas Family Residential Center were about a thousand people were incarcerated as of late March. Activists went to both sites there and then came to the detention center with thousands of handmade paper cranes to place on the fence as a symbol of solidarity with the moms and the children confind inside. Can you talk about that? What was that experience like for you and the others who were there?

CO: This turned out so surprisingly relevant, you know, because originally a small group of us said we would like to do a pilgrimage to Crystal City. Pilgrimages have been happening within our community for a number of years and we go to Tule Lake. We go to Manzanar. We go to Topaz and Utah. Crystal City is one that is sort of an obscure story. So it's not been on the map more or less. But this time we decided that we wanted to do that. So a small group thought we would plan a larger pilgrimage which will happen in November. And then as long as we were going there, we decided that we would also go to Dilly which is a detention center, supposedly the largest one in the country, holding families with children.

And one of our members got this great idea and he said, we will go and demonstrate and we will festoon the gates — the fence that surrounds this detention center — with paper cranes. And he said let's ask for 10,000 paper cranes to be made. And I thought, “He's crazy,” you know 10,000 paper cranes. And we only had maybe a month or something to do it. Well, with social media and all it just mushroomed and over 25,000 cranes came and they're still coming evidently. Yeah, being sent down to this place in Texas. And then beyond that arrangements were made for our group to visit with what they call the Mexican Caucus of the state legislature there in Austin, so we had a meeting with those legislators and they were of course astounded at the story.

I mean, they didn't know what Crystal City was or what and here they were very close by. And then we also visited sanctuary churches there in Austin and met some of the people who are currently living there in the churches. And also a part of our group went to Laredo, the border and another thing that some of our group did was to go to the local Greyhound bus stop where people who are released from Dilly are sent there with their tickets. They have sponsors usually but here are these people who don't speak the language, who are here with nothing more or less. They said you can tell because they might have a brown paper bag with their worldly goods. There are volunteers there that help orient them like, you know, which buses or whatever transportation that they're using to get to their destinations and also to give backpacks to the children with some toys and some goods that they might need so these are all fairly well-organized and I'm really amazed to see how many volunteers there are who are daily practically helping as much as they can, given the situation.

RA: Gilda, what are your thoughts about these expressions of solidarity, you know people like Chizu, taking a trip to Crystal City and then also trying to get to the family residential center, that's what it's called in South Texas, to express solidarity with migrants?

GTM: I think that it's really essential because if we don't have the type of support, I don't think that is a lot of hope for those families, for those people. I think that I remember when I first, when I was in this place, we would have people that will volunteer their time like counselors and everything — their time to speak to us, right? Just having those people that really want to help. I think that that's the thing, an act that it can provide us like the people that are there hope and really feel that people care about their struggle and there are people that really want to help as well.

Chizu Omori’s Story of Life in Internment

RA: And let’s talk about your personal stories. Chizu, your family was forced out of your home in Southern California and sent to the – is it Poston?

CO: Yes.

RA: The Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona and this was in 1942. You were only 12 years old. Your sister Emiko was one and a half and at its peak population nearly 18,000 people were imprisoned there. The U.S. Army directed the forced relocation efforts. People had six days notice. So your family had only six days to dispose of belongings other than what you could carry?

CO: Well, that's an arbitrary figure. Six days, I mean, you know, there were different situations for different people. It was longer than that for us, I believe. Yeah, but not very long, you might say. Actually at Terminal Island, I think those people were just kicked out immediately. We were put on trains and we went directly to Poston, Arizona. That's one of 10, what they called relocation centers at that time. Most of the other people though had to go do what they called assembly centers, and those were makeshift housing you might say, like at racetracks and fairgrounds and just anyway, very temporary kinds of places where people were literally housed in horse stalls. And they were left there while the main camps were being built in the interior. Some people really got moved around a number of times. My family stayed in Poston for the three and a half years – the duration of the war. So I think that we were somewhat luckier than others...

There were also, well, we're not quite sure or I'm not quite sure, a number of Department of Justice camps, which were different kinds of camps. These men who were rounded up at the beginning that I spoke of, they went to DOJ camps. These were for aliens because our immigrant parents could not become citizens at that time. There was no, you know naturalization. So that whole generation were not allowed to become citizens. So these DOJ camps were pretty much for the so-called alien people. But they set up a number of different kinds of camps, like there were camps at places called Moab and Leupp, which were for troublemakers in the camps and those were for citizens, mostly men. They were just summarily picked up and dumped into these camps if they were causing too much trouble. They moved people around a lot depending on the circumstances.

RA: What was life like in the camp that you were in and what were the conditions like?

CO: Well, the camp really was not finished when we got there. So there was still construction going on. Everything was very raw. They’d just taken bulldozers and just scraped the land and just built these barracks on top of the land. So we're walking around in just soft sandy soil. I mean you’re just plunging into this stuff and when it rained it just turned into mud. So it was just a big mess and the barracks were very flimsy so that dust could come through all of the cracks in the knot holes and such. This is a life which is very regimented like the barracks were divided into four units and it was five persons per apartment as they called it. Arbitrarily there were couples who are moved in with other couples say to make up that component of five. And then other larger families maybe got two rooms. But it just was, I guess you could call it pure communism or something. Everybody was equally miserable and the middle of the blocks – the blocks consisted of about 14 barracks and there was one big mess hall to feed all of the members of the block and in the middle of it there would be a men's latrine and a woman's latrine and one wash house for doing laundry. And I think each barrack maybe had one faucet of water. We had I think, one or two light bulbs hanging from the ceiling, so they were extremely bare when we got there. So one of the first things that people did was try to make their quarters livable. So they took the leftover lumber that was around and just built furniture and interestingly people became very creative and you know some people really made some rather nice furniture and whatnot. This regimented life was just so different from what we were used to. I think the amount of leisure, if you could call it that, just down time, there was a lot of it, because you didn't have to bother with cooking or anything. You just went to the mess halls to eat. So people did a lot to fill their empty time spans. So right away, social organization took place. Churches, sports teams, social clubs of various kinds and so they made the best of the life that we had there.

RA: And your mother passed away two years after you left the camp. She was 34.

CO: Yes.

RA: And then you've said that your father really never talked about what happened.

CO: Talk...well, you know, I know that the silence in the families was you know, kind of standard. And you know, I look back on that and I think that it was very painful for most families. That it's not something that they wanted to dwell on or to discuss very much. So, yeah, I think it was an attempt to re-establish our lives and it was just better not to dwell on the past.

RA: It's so interesting – that seems to be a theme during the shows that were doing. When we had on Norm Ishimoto a couple of months ago, he said his parents really didn't talk about it. In fact, he learned more after they passed from trinkets and things that they had saved, and I think it may have been one of the first times he publicly spoke so intensely about it and it was really, really emotional for him.

CO: Yeah, of course, this isn't true of everybody. But this is the way I look at it now: many of us, you know, we know the small picture. We know the particular camp that we were in and what happened in our camp, but to see the overall picture — the big picture, the government and its policies and such — that was hard to do. And at the time of say, you know, like post-war there was really no way to know very much about that. It is just taken years of digging and everything so that we have a clearer picture of what happened. Yeah, and the more I know, you know, the madder I get about the big picture because I think the government was really very repressive and they almost succeeded in destroying our community in the sense that I think they made us question our identity. Like, who are we really, you know, if we're Americans, why did they do this to us? So if we are, say Japanese, you know, which is the culture of the country that our parents came from, then we were the enemy during World War II and therefore it was not safe to identify with being Japanese. But anyway all of these questions were heavily on our minds and the government exploited a lot of these confusions.

RA: Chizu Omori is a writer and activist based in Oakland. When she was just 12 she and her family were forced from their home in Southern California to a Japanese internment camp in Arizona in 1942. Chizu is part of the Nikkei Resisters. That's a group of Bay Area Japanese Americans who use the legacy of internment to show that civil liberties can be taken away at any moment. They also join in solidarity with oppressed people. We're also joined by Gilda Temaj Marroqin, a student in the Ethnic Studies program at UC Berkeley. Gilda came to the United States from Guatemala on her own when she was 16 years old – that was six years ago. She was briefly detained in two different facilities before she was able to move to San Francisco.

Gilda Temaj Marroqin’s Story and Her Journey from Guatemala to the U.S.

Gilda, why don't we talk about your story? And do you mind talking about why you decided to leave Guatemala on your own six years ago?

GTM: I decided to leave because growing up in Guatemala, I was one of nine siblings and my parents were really poor. And besides that, I think that being a woman in Guatemala was just...my dad really had this idea of like how men were superior than females, right? I have two older sisters that went to school for six years. And then when you turn 11 — that's when you are about to finish sixth grade — what happens to you as a woman back home was that you get taken out of school. That's what my dad did to my older sisters and then you are at home, just waiting ‘till you can get married and then you can go and live with your husband and have kids. And that's how it is like back home.

So, I never thought that was going to happen to me, right? I was just a kid. That I was working with my family. I was doing all these things and then when I turned 11, I didn't want to think about it, but it happened. My dad is like, “No more schooling,” and I was like, “No, I really really want to go to school. Like I think I'm a good student.” And my teacher also back in Guatemala talked to him and he's like “No, like this is how things are, like you can stay at home, learn how to do the chores, just getting ready,” right? And at the beginning I tried to fight him back, but I knew that my sisters agree with [him], the older ones. They were not doing anything. They were just there. And I was like, why would I be going against this, if this is a cultural thing, that this is my dad’s decision, right? So I stayed at home trying to be a housewife, taking care of my younger siblings as well for five years. Yeah, I was just there. But I always questioned everything. I was like, why is it that my brother is going to school and not me? Like why is this? And I disagree with this. And yeah, I think there was a turning point when I decided to leave, I saw students that went to school at the same time that I did, and they were mostly males, like moving farther in their education, right? And then I was 16, I was about to turn 17, when I told my dad I was gonna be immigrating to the United States. My brother was here. So I was like, I'm going to go with my brother. And my dad just laughed at me, and was like, “You’re not going nowhere.” And I was like, “But I am. Like I think that I'm old enough and I'm leaving. Here I don't see myself like following the same steps as my sisters. And I don't want my kids to grow up the way I did. And I want to provide for my family and I want my younger siblings to have more opportunities than I had. And I have all these ideas, right? Become independent, like live my own life and I'm like, I'm gonna go there get a job, and and I'm going to come back and I'm gonna come back and I'm gonna have more. I have a voice in this family. I'm gonna do these things. And at the beginning he's like, “No, you’re not leaving, like this is not happening.” But I think that afterwards he realized that I was not going to give up on that like I was not – that was the thing that I just decided to do and I was going to leave.

And it was hard, like I think it's hard to convince my dad to let me leave. I said that, “Even though you're not going to, with your permission or without your permission. I'm leaving.” And eventually, he decided that he was just going to let me, let me go right? And then – so I left. I left and they didn’t know anything. Now that I think about it, I'm like, “Damn, that was so hard! And that was an interesting decision.” My sister now, the older one is 16. She's in school now, so that’s one of the things that has changed about home now. But I'm like if she decides to leave and knowing what I know now about the journey, I will be, “No,” because it's hard. And so now I understand why my brother didn't want me to come at the beginning. He's like, “It is hard. Like it's not that easy and everything.” But I was like, “But I really want to leave.”

So I left. From Guatemala I crossed Mexico. I think it took me like three to four days to get to Mexico, right? And then I was in the Mexican border for a long time. I run out of money. I had to call my brother to borrow more money and there's not a lot of like stores. There’s not even banks, that people said money and then you have to be waiting in these long lines. I remember that people sleep on these huge lines [waiting] for the bank to open. And I was doing that because you have to pay in order to have this little space that you can sleep and you also have to pay for your food each day, right? So I was just so worried because I ran out of money at the border. And I'm like, what am I going to do? What’s going to happen to me? Where am I going to sleep? When am I going to eat, right? All these questions. So my brother sent money, and then what happened was that I was in line waiting to get to the door and get the money ready, right? ...My brother is like, I already sent you the money, and then I think they [were] like two people in front of me when the bank said, “They had no more money,” that they ran out of money. And I did cry. I was like damn, what am I going to eat now? What am I going to do now? Where am I going to sleep? But I had this person that I was talking to. We met there and she's like, “I'm gonna borrow you the money that you need for this night and then you just going to stay here.” So I stayed there and I waited. So it was tough.

People had other stories and ideas where they were going to go, because we were there for so long. People were getting desperate, getting tired of being there, running out of money. They didn't know what to do. But I mean, I stayed there for yeah, about a month at the border of Mexico. Then we...like we we started to walk, right? We started to walk. I think we walked for five to six days. And then it happened. I think I was at the U.S. border. And then that's when I got detained. And yeah, they took me to this place that was bad.

RA: And before you talk about that, do you remember how many days you spent walking?

GTM: Yeah, like five...five to six. Yeah, it was almost six days when I got...when I got detained and were going to be six days.

RA: But what about just leaving home?

GTM: Oh leaving home. Oof. [Sighs.] Two months, I guess. Like two months, like my family didn’t know about me. I didn't call. They didn't know what was happening to me. It was only my brother that was aware of where I was going... I mean, I didn't want to call home either because my dad was not happy with me leaving. So what would be the point of me calling back to tell them, hey, like I'm having all these issues and all these problems? One, they couldn't help me out, and second, like I didn't even know how they would react. So it's like... I don't think…

RA: What did your mom think of your decision?

GTM: My mom...she’s great, but I think that my mom does whatever my dad tells her to do. So she has no voice in the family. So yeah, disagree or agree, I think that it doesn't really matter because the last word – my dad has the last word. So yeah, she, she was sad. She was sad. She didn't want me to leave but there was nothing she could also do.

RA: And so your brother was already in the United States. What did you hear from your brother? I mean he said it would be really hard. But what else did you hear about the United States and what it would be like if you made it?

GTM: If I made it, I mean what I do here… What did I see back home is that people were helping out their families, like people were providing for their families. So I thought that there was work. There was work in the United States. I don't know what type of work I was going to be doing at 16. But in Guatemala there were no jobs, no opportunities. Like at least I'm going to be able to help my family out financially and I think that all this motivation and all this eagerness of going out there and making money was because I think that's what my dad valued a lot. Like, my dad is like, “Oh see your brother like is helping the family out, and you’re just gonna wait until you get married.” I'm like, “No, I think I'm just gonna go there and do the same thing and really show you that I also have power that I also like can can do things.” So, yeah.

RA: And when you were detained like so many other people, you didn't know how long you would be there, right?

GTM: No.

The Enduring Ripple Effects: the Breakdown of Identity and Family

RA: I mean that's another parallel, right Chizu? People who are detained they have no idea what's coming. Did you all know how long that you were going to be in the camp?

CO: Course I was just, you know a kid.

RA: Right.

CO: And in my family, I think we were fortunate that my parents were kind of calm and not easily frightened or whatever, but I've heard stories of other parents who thought that we were all being taken out to be killed, to be shot or whatever and like, don't eat these lunches because they might be poisoned. And anyway, so we really didn't know where we were going and how long we would be there. I mean, it's just, you know, like our whole lives were...we had totally lost control of our lives. That had to be very hard on parents.

RA: Chizu Omori is a writer and activist based in Oakland, and when she was 12, she and her family were forced from their home in Southern California to a Japanese internment camp in Arizona in 1942. We're also joined today by Gilda Temaj Marroqin, a student in the Ethnic Studies program at UC Berkeley. Gilda came to the U.S. from Guatemala on her own when she was just 16. That was six years ago. And this is a special live taping of Your Call. We are at Mission High School in San Francisco. It is part of our series, HEAR: Histories of Exclusion and Resistance, and we have a question from an audience member. Hi, would you state your name?

Lisa: Yes. Hi. My name is Lisa. My father was living in Seattle. And he and his mother and brothers were taken to Minidoka, which is a camp in Idaho. And he had an interesting situation where he was there for I think about a year and the family actually was as opposed to many of the people were Buddhists. They were Episcopalian and there was a Episcopalian family in Ohio who offered to take someone from the camp and it happened to be my father and his mother and they left the camp early and moved to Ohio, which is an example of people doing something to actually help these families. The other thing I wanted to say was...in the camps, I think my understanding – and I've been to several of the pilgrimages – is that there was a breakdown of the family. The family structure was broken because the parents — the Issei who really lost so much throughout this — they didn't have, really, their identity. And there was really very little for them to do and so the family structure, really, really fell apart. And, and then you think about mental illness and you think if you hear about people right now in the detention centers, families being taken away, and oh my goodness what's going to happen? Thank you.

Loyalty Questionnaire: No-No Boys

RA: Thank you so much. Chizu, what about the long-term effects?

CO: It's pretty traumatic like the things that happened to us. One of the issues that I have been particularly interested in is that there were, there was a group of young Japanese Americans who had formed an organization called the Japanese American Citizens League, and the government allowed them to be the spokespeople for our group. And they had the belief that well, we need to show our loyalty. We need to show our patriotism. We need to show people that we are real Americans and the way to do that is to take all this in stride and show that you know, we really are loyal. And one of the ways to do that is to serve in the Army. After all, here we are, all you know in the camps and I think the idea that this group really wanted to have the young boys serve to show their patriotism and loyalty, you know, was just crazy. Why should they go and die in the American wars just to prove that we were patriotic Americans?

And one of the ways that the government decided to determine loyalty and disloyalty was through a questionnaire that was administered in early 1943, and that originally was for just men of draft age and they allowed for volunteering for the Army. And the questionnaire then was administered by the War Relocation Authority. And they labeled it application for leave clearance. They thought that if they had a document that showed that you were loyal and you could leave the camps. It was just supposed to be a way of getting more people moved out of the camps, but then the two questions that they used as kind of how to distinguish loyals from disloyals. The first question was 27 – was will you serve in the Army? And the second question was would you forswear allegiance to the Emperor of Japan and swear loyalty to the United States now? If you were no no's on those two questions, you were automatically considered disloyal, and if you like said yes but...you know I'd be willing to serve if we were allowed to leave the camps and our civil rights were restored that put you in a category where you were questionable. When they you know took all the questionnaires and coded up the loyals with the disloyals, they turned Tule Lake into a segregation camp for the disloyals. So that meant a big transfer of like 12,000 people from the other camps and some people from Tule Lake moved into the rest of the other camps. Anyway, that was a watershed moment for our community because forever people in Tule Lake were labeled disloyals which made them pariahs within their own communities.

RA: The question about allegiance to the emperor of Japan is very strange. I mean sixty percent of the people imprisoned were US citizens.

CO: Yeah.

RA: And and I've seen some documentaries where people said, “Why would they even...we don't even know who they're talking about? This is such a strange question, the Emperor of Japan.”

CO: Yeah, and they had no recourse to legal advice. And this was mandatory for everyone over the age of 17. I fell under that age limit. So I really didn't know very much about that going on because I didn't have to submit. Yeah. However, what happened in that case is my parents got very angry about it and they decided to...they didn't want to stay in the country anymore. So they signed up for repatriation to Japan.

RA: Gilda, did you have to meet any requirements to be released from detention?

GTM: They asked me if I had someone that would take care of me, that will send me to school, that would be taking care of me. And if I was going to enroll in school. I think that that was one of the main requirements that if I was going to do this, then I was gonna be able to be released.

Gilda Temaj Marroqin on Life in Detainment

RA: We've done a lot of shows about the conditions of these places. What were the conditions like when you were there?

GTM: For?

RA: In the detention center.

GTM: In the detention center. At the beginning I was placed with everyone else. My group got everyone, got advisors. We got placed in this place at the beginning and I was there for a day and that was not…that was bad. There were not giving us food and then they were not giving us enough water, and there was no like blankets or anything. You had to sleep on the floor and you were just in this room with so many other people and you didn't know what time it was. So I was I was just surprised. I didn't know why I was there. Like I want to...this is not where I was supposed to be going and everything. But then after that, they asked for my age. And after they asked for my age, they filled out paperwork and then they moved you to this different shelter.

And then when I got to this shelter ...they gave me food, and there was a place to shower. So I think there was a bed. So I think that the condition for us minors is better and but also like one of the things that I didn't...I felt that you were in a way free. But there were still like people that are like... walking around 24 hours, so checking, counting you if you were still sleeping and everything because there were stories of how people would try to escape the shelters because they wanted to go with their families.

So I think that yeah that not knowing what's going to happen, like it's just this feeling that people were crying. People were crying saying that they've been there for like months that they didn't know what's going to happen to their cases. They were afraid of going back and just hearing those stories I was just what's going to happen to me also. Like yeah, so it's just a lot going on in that place.

RA: And so because your brother was able to sponsor you, you were able to leave, right?

GTM: Yeah, that’s right.

Acts of Resistance in Japanese Internment Camps

RA: We have another question or a comment from the audience. Hi.

Emiko Omori: Hi, my name is Emiko Omori and I'm Chizu’s sister and I was in camp as an infant. Since there are these two things, I have these various questions. One irony was that Poston, Arizona was on an Indian reservation. And Chizu recalled that you know, Indians would come to see us and we looked at them through the fence and you know, we all felt like outcasts together. The other thing that I needed to find out when my sister and I made this movie, Rabbit in the Moon, was that there was a lot of resistance. We had from many years bought what I would call the government version and that was that we all went quietly. It was our patriotic duty, but when we started looking into the history there was lots and lots of things going on in camp in every camp.

For instance when the draft came through, and Chizu, you have to correct me and I think it was at Topaz, there were a thousand Issei, that’s immigrant mothers, who signed a letter to send to President Roosevelt about not having their sons drafted. There was something referred to as a Manzanar Riot. Well, it really wasn't a riot. It was more a protest that took place in camp where two people died, shot by the military police, and we are compiling right now a list of all the resistance actions that took place, and one of the reasons we are now supporting the immigrant asylum seekers is because when we went to camp, no one really came to support us.

I mean that isn't to say no one came. The Quakers were very sympathetic and sent Christmas presents to the children in the camps, and two particular lawyers and mostly the ACLU of Northern California, Ernest Besig, was a man who saw that this was wrong and the national ACLU threatened to expel the Northern California ACLU if they took any cases of which Ernest Besig said, “No, this is wrong.” And he is the one that found Fred Korematsu in a jail and convinced Fred to be the case that would go to Supreme Court. Of course the whole Supreme Court thing is yet another story.

Anyway, as a child growing up in the ‘60s, resistance was very important and there's draft resistance, and it you know, because we were kind of seen as the model minority, quiet and all that, and that that's like a straightjacket. So I was very pleased to learn that we had fought back.

RA: Thank you Emiko.

EO: I would like to make one little comment. The situation with Muslim Americans is also very concerning, and I know we're focused a lot on the border situation because our president insists on talking about it daily. But I think that the Muslim community is facing a lot of the same kinds of challenges that we faced and there's a lot of deportations and all that but they're being scapegoated as terrorists, you know, or possible saboteurs of various kinds and so they're facing the same kind of scapegoating.

RA: Right.

Gilda Temaj Marroqin on Creating a New Life in a New Place

RA: Let's talk a little bit, Gilda. We don't have that much time left. But when you left the detention center to live with your brother, you basically were starting a new life in San Francisco at age 16. You went to San Francisco International High School, a multilingual school for recently arrived immigrants. What was that like for you? A brand new country, a brand new city, new people.

GTM: It is tough because I think that right now my brother and even my family are...they are proud of what...how much I have done, right? But they also feel that I'm... I'm in a way betraying the family because I am not doing what my brother's doing or what the rest of the people that move here are doing.

...How did this happen? Going back to how this happened is that the school where I went to, I think that there is a lot of support and people that really care about us —the students — that they understand: where we are coming from, our struggles, why we decided to come here. So I think that in this high school, they really focus on you as a person but also they understand your different struggles. They understand that you are going through this immigration status issue, right? You're working on that. You’re also learning a new different language, right? So I think that one of the things that my high school, I don't think they care about the students but they also know that there is a huge gap that they are filling, because they are teaching us the language, but they also are preparing us for college, right? So I never thought I was going to go to college. ... I'm like...I'm...I was 16. So I was just waiting to turn 18 so I could drop out of school because they told me like if you’re enrolled in school that's the only way you can ever be able to be with your brother, but then they told me that when I turn 18, then it’s not required. It was not mandatory, right? So I went to school. I was like I’m only going to turn 18 and then school is not in my plans, right? But no things work out, they work out, that the people are helping me in the community also that I seek a lot of resources in the community and to the point that...that I'm here now.

Sparking Resistance Today

RA: Emiko brought up resistance, and I'm sure a lot of people in the audience are just wondering what can people do? And one of our last shows a young woman from El Salvador came to the Bay Area and a family in the East Bay sponsored her while she figures out what's next. But what would you say, just quickly, what can people do to step in and help? What's what would you say is most effective, Chizu?

CO: Well, you know, I'm an old activist and so I think politically we really need to get active and we need to hold our politicians’ feet to the fire and insist that...insist on some decency and some common sense in dealing with these situations. I understand they’re difficult. But you know as a nation, where's our compassion? Where's our understanding of immigration, which is the story of America after all.

RA: Thank you. Gilda, what would you add?

GMT: I'm able to be here because of all [these] people that are volunteering their time. And also like supporting us financially and just providing more opportunities, I guess that the support is really essential, like really giving back to the community and I also believe in giving back to the community. Also working hard. I think that the people that are able to come here, I think that shows really take advantage of this opportunity, just make the most out of it and in that way we've been able to just help the people that come in behind us as well.

RA: I want to thank both of you so much for joining us. Gilda Temaj Marroqin and Chizu Omori. Thank you both so much for joining us.

Unfortunately, we are out of time. Your Call is a production of KALW public radio in San Francisco. This series is made possible by the California State Libraries, California Civil Liberties Public Education Program. Special thanks to Mission High School. Especially history teacher Robert Roth and Principal Eric Guthertz. Thanks also to everyone who helped bring the show together. Laura Wenus, Phil Surkis, Taylor Simmons, Laura Flynn, Kristen McCandless, Lea Ceasrine and Brieanna Martin. And thank you all for coming today. Thank you so much for joining us. I'm Rose Aguilar. It's Your Call.

Credits:

Rose Aguilar, host

Laura Wenus, producer

Laura Flynn, project producer

Phil Surkis, assistant producer

Taylor Simmons, social media manager

HEAR is made possible by funding from the California State Library's California Civil Liberties Public Education Program.