This story originally aired on August 22, 2019 and most recently in the August 7, 2023 episode of Crosscurrents.

Our stories are made to be heard. If you can, listen before you read.

In classrooms nationwide, students are learning to pay attention to the present moment. Focus on their breathing. Notice if they’re bored. And consider what that feels like in the body. One San Francisco volunteer walks kids through mindfulness practice.

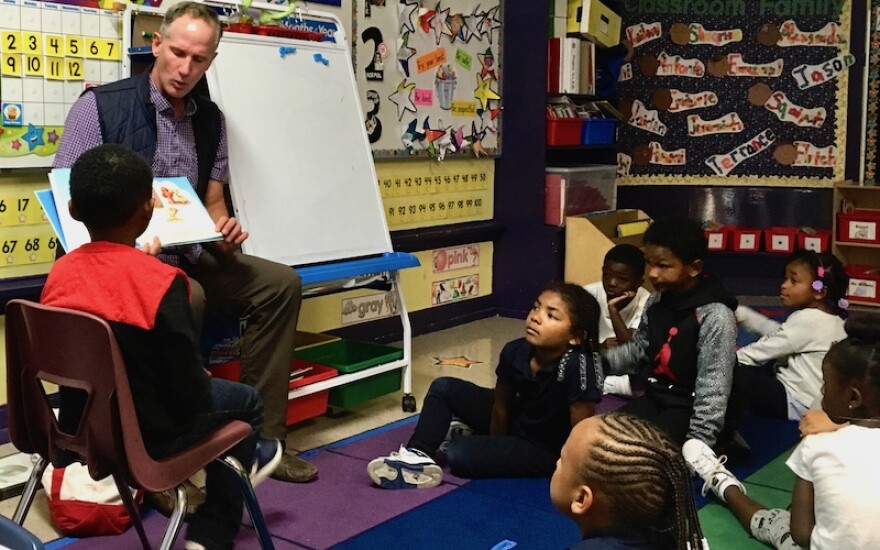

Andrew Nance just finished taking attendance in this first grade class at Bret Harte Elementary School. He tells the kids to sit up nice and tall, take some deep breaths and wiggle their toes. Just about all the kids are mesmerized.

“Remember, nice slow breaths,” he reminds them as one boy lets out a sing-song exhale. “Our puppy minds like to do everything fast.”

Nance is the founder of Mindful Arts San Francisco — a nonprofit that’s bringing mindfulness practice to more than a thousand kids at about a dozen schools all over the city. Like Nance, all the practitioners are volunteers. Here at Bret Harte, all the kids know him as Mr. Andrew.

As he asks the students sprawled on floor mats to switch to “breathing ball breathing,” one boy sitting in a chair kicks it. Over and over, in a steady rhythm. Mr. Andrew doesn’t tell him to stop. Instead, he asks the boy to notice what’s going on inside him.

“Jaiden, how you feeling? You feeling frustrated today? Or good?” he asks, as Jaiden softly answers: “Frustrated.”

In mindfulness practice, there are no wrong answers, and by identifying his emotion, Jaiden’s doing great. Mr. Andrew moves on, but keeps Jaiden close, as his helper.

Mr. Andrew is tall with a warm blue-eyed gaze. He carries two things into class with him — a stuffed puppy and a book he wrote, called "Puppy Mind." It translates the value of being in the present moment into kid speak.

The 'puppy mind' is the wandering mind. Mr. Andrew wants the kids to know that if they can learn to be aware of their puppy minds, they’ll be able to make better choices. Just like the little boy in the book.

Mr. Andrew reads on, his voice reflecting his decades spent on the stage. “When my puppy mind is bored it runs to the future and the past. Whoooosh.”

For nearly 20 years, Mr. Andrew directed San Francisco’s New Conservatory Theater Center, working with a lot of kids. But six years ago he decided he was ready for a change. During a mindfulness class, the instructor introduced some theater games.

“That's when the light bulb went off,” he says. “Mindfulness training and theater training are so similar, it asks you to be in the present moment. It asks you to use your breath to get focused. It asks you to connect with the other person in front of you.”

Nance signed up for an online mindfulness training course with mindfulschools.org, which since 2007 has trained educators all over the world. Almost right away, he was volunteering with two pre-Kindergarten classes. But when he searched for books for little kids, he says, he couldn’t find any that he liked. That’s when "Puppy Mind" was born. In the book, as the little boy’s puppy mind wanders into the past, it stirs emotions.

“My puppy mind can dig up memories, like when I got yelled at for not sharing my things,” Mr. Andrew reads to the class.

“What’s he feeling? What’s our boy feeling?” he asks the students.

“Crying,” one boy answers.

“What’s the emotion?,” Mr. Andrew probes. “Sad,” a few students call out.

Mr. Andrew developed a curriculum using storytelling, theater, and art projects for all elementary levels. (It was published last year.) And four years ago, he started visiting Bret Harte Elementary, in the city’s Hunter’s Point district. Today, Principal Jeremy Hilinski has welcomed him into every classroom. Hilinski says mindfulness has turned out to be a great tool for kids whose families cope with a lot of stressors. For example, he says, many work multiple jobs and still unable to make ends meet.

Trauma and adversity also play a role. Gun violence -- either in the neighborhood or directly affecting a student -- happens five or six times a year, Hilinski says. That kind of ongoing stress can impact a child’s brain, make it hard to concentrate or settle down. And kids here have plenty of meltdowns. But Hilinski says he doesn’t feel that “depending on the parents to manage self-regulation is the way to go. We have the kids essentially more than they do. It just doesn’t work.”

Instead, he says, “We need to figure out solutions that work here and we need to be creative about it.”

Enter Mr. Andrew. He spends just 20 minutes a week in each class. But Hilinski says,”The kids are now older and are using it and, not surprisingly, have far fewer issues in self-regulation.

Mindfulness is rooted in Zen Buddhism. But in the 1970’s Jon Kabat-Zinn adapted it for clinical use to treat adults with chronic pain. His technique, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, led to a mindfulness explosion in other settings. It’s used in corporate offices, and in jails and prisons. In public education, it’s part of a larger philosophy: That teaching students to be conscious of their emotions is key to learning. The main goals: to increase self awareness, concentration and wellbeing, and reduce anxiety. Including in the classroom.

But there are some concerns. This work doesn’t require a credential. And classroom activities referred to as mindfulness-based are all over the map. Most importantly, psychologists warn that practitioners need to be careful with students who’ve suffered from recent trauma. Their defense systems are in place for a reason. Being forced to sit with their feelings could be harmful. Mr. Andrew agrees. He never insists that kids close their eyes or do anything.

“Mindfulness is always an invitation,” Nance says. “Often in trauma-informed practices, you can just invite a student to look for the most pleasant thing in the room, as a way to be focused and in the moment.”

Nance says he never judges a child’s reaction either. Because mindfulness is a noticing practice, not a calming practice.

“Do you feel like your heart is open or closed when you're angry? Do you feel warm or cold when you're angry?” he says. Those kinds of questions aim to help kids match the sensations to the blooming emotion, “so they can go, uh oh my shoulders are up, my face is getting hot. I'm going to take a deep breath so I can be a little bit more skillful with this anger. Not to get rid of it, not to say it's not valid, but not let it run the show. You get to run the show, not anger.”

Back in the first grade classroom, the little boy named Jaiden is helping Mr. Andrew turn the pages of "Puppy Mind." He still seems frustrated. But he’s paying attention. And taking part. The class is talking about where each kid’s mind might lead them in a daydreaming escape.

“Where would your puppy mind take you, Jaiden?” Mr. Andrew asks. Jaiden whines as he answers, as if he carries the weight of the world. But he answers: “To the dirt bike storrrrrre.”

“Perfect,” Mr. Andrew replies.

Even advocates for mindfulness in schools agree the enthusiasm has moved faster than the research. But one study of Oakland students showed that kids in the mindfulness group were better able to pay attention, participate in class more and show more consideration to others. A more recent clinical trial of high-risk youth in Baltimore found that mindfulness improved posttraumatic stress symptoms. And, none of the students in the mindfulness group showed negative effects.

Mr. Andrew is getting close to the end of the book, when the boy tames his puppy mind and they fall asleep together.

“The puppy mind is strong. But you guys are stronger,” he reads.

Before he leaves for the day, he plays a mindfulness game with the class. They’re supposed to stare straight ahead and not look behind them, even as Nance makes kitten sounds and tries a bunch of other tricks to break their concentration. They do pretty well.

“They're kids,” he says in an interview. “They're not supposed to be perfect. And who wants to be perfect? But they do need skills. And telling a kid to calm down is not a skill.”

Chastising like that, he adds, is also punitive, “like ‘I’m watching you so calm down or I will get upset.’ You know, who are you if no one's watching?”

That’s the skill that he wants to teach these kids — how to be kind to themselves and others when no one’s watching.