It's been a year since President Donald Trump signed a package of bills called SESTA-FOSTA to crack down on sex ads online. Supporters said this package would combat sex trafficking. Critics said it would only make the sex trade more dangerous.

Nine years ago, Vanessa Russell learned that one of her dance students was being trafficked and sold throughout California. The student was 15 years old at the time. Russell was horrified and went looking for her on the streets and online.

“I would go to tracks and blades where people are sold, and I would notice that there were many young kids there,” Russell says. “My eyes were open to the reality that this was not some anomaly.”

Russell looked for her student on sites like MyRedBook and Backpage.com, two major platforms for sex ads at the time. She was disturbed by the images she saw, including ads for minors.

“You click the link, and someone is having sex right there,” Russell says. “You see it. You see acronyms that say whether she requires condoms or not. And this is of a child that’s being raped.”

Russell, who was inspired by this event to launch Love Never Fails, an anti-sex trafficking advocacy group, was shocked that these ads were so readily accessible to anyone looking to exploit children.

Pressure mounts

Over time, mounting pressure and lawsuits from victims’ families forced investigators and lawmakers to act. In 2016, 16-year-old Desiree Robinson was found beaten and stabbed to death after being advertised as a prostitute on Backpage. The victim's mother filed a wrongful-death suit against the site, and this case and others helped fuel nationwide outrage.

That same year, then California Attorney General Kamala Harris charged the website's CEO and owners with 26 counts of money laundering and 13 counts of pimping and conspiracy to commit pimping.

“My office will not turn a blind eye to this criminal behavior simply because the defendants are exploiting and pimping victims on the internet rather than on a street corner,” Harris said at the time.

Backpage had been shielded for years from such charges by the Communications Decency Act, a 1996 law which protects websites from liability for material posted by users.

The raid, and the alarm bells

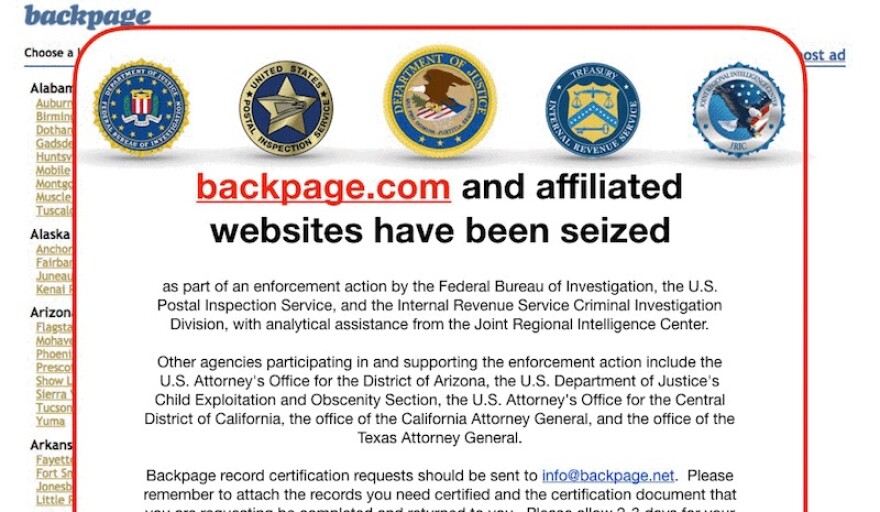

The U.S Justice Department finally seized Backpage in April 2018. Just days later, President Trump signed a sweeping package of bills to make it easier to prosecute sites “knowingly assisting, facilitating, or supporting sex trafficking.”

The package, known as SESTA-FOSTA, empowers states and victims to sue online platforms for facilitating and assisting sex trafficking. Supporters hailed the law as a victory for victims and survivors, but sex workers resoundingly condemned the move. Many saw it as an attack on their businesses and their safety, and warned of the dangers of conflating sex work and sex trafficking. In anticipation of the law, Craigslist shut down its personal section, and Reddit removed several subreddits related to sex work.

In response to the bills, the group Collective Action for Safe Spaces tweeted, "Sex work is consensual. Sex trafficking is coerced. The crackdown on Backpage is not about ending trafficking; it’s motivated by the patriarchal notion that women should not be free to do what we want with our bodies."

One year later

One year since the passage of SESTA-FOSTA, some sex workers say the measure has made it harder to screen clients and stay safe. Sex worker advocacy groups say the shutdown of Backpage hasforced more people to rely on pimps and work on the streets, where some studies show the sex trade can be even more dangerous.

“I can’t tell you the number of us that were affected when this nightmare began to play out,” says Kristen DiAngelo, co-founder and executive director of the Sex Workers Outreach Project Sacramento chapter. “It’s not about the safety of the people who really need the help. Things haven’t gotten better; they’ve gotten exponentially worse.”

From newspaper ads to the internet

This kind of crackdown on platforms advertising sexual services worried DiAngelo, but it did not surprise her. She says she entered the sex industry decades ago when she was 16 years old. Her parents had left the country, and she needed a job. When she saw a newspaper ad for a job at a massage parlor, she took it.

“You can’t forget these things, because they change your life,” DiAngelo remembers. “I found out really quickly I could survive. I could make money.”

But after a crackdown on massage parlors and sex ads in newspapers, DiAngelo no longer had a way to advertise and was forced to rely on pimps to find clients on the streets.

"I became desperate because I had no way to support myself," DiAngelo remembers. "A girl said, 'I know a guy who can help you.' And that was the beginning of me being trafficked for the next ten years."

DiAngelo says she was beaten and raped but was told police would arrest her if she ever reported the assaults. She was eventually able to escape the sex trade but went back to the sex industry as a consensual sex worker years later.

“Because these are my people, and these are the people who understand me,” DiAngelo says. "This is where I belong at this point in my life.”

The rise and fall of sex worker forums

The sex trade had also shifted dramatically since her first job at the massage parlor. In an interview with Motherboard, DiAngelo describes how sex workers used the internet in the early 2000s to advertise their services, even coding the pages themselves.

The Mountain View-based site myRedBook launched in 1999 as a forum for johns to post reviews of escorts, according to Wired magazine. It grew as a platform for sex workers and their customers to connect and exchange detailed reviews of each other. This became a valuable way for sex workers to build a sense of community, and warn each other about dangerous clients. By 2004, Backpage was launched, and sex workers used this site as a tool to advertise online.

“A lot of folks who had been working outdoors were actually able to take greater control over their ability to advertise themselves,” said Pike Long, the deputy director of St. James Infirmary, a peer-based health and safety clinic for sex workers in San Francisco. “Sex workers were able to start screening clients, weed out the guys who did them harm, and catch people who had been harming sex workers.”

But these sites also became an easy surveillance tool for law enforcement to perform sting operations. The platforms also caught the attention of federal lawmakers. In 2014, two men suspected of running myRedBook were arrested, and the site shut down.

“We watched a series of stings. Sfredbook, and rentboy.com got hit...It was like bam, bam, bam. This was the beginning of the internet raids,” DiAngelo says. “48 hours later, we had young girls hitting the streets for the first time. We had two women off the streets for nearly a decade that had no way to survive. We had mothers crying.”

As a way to advocate for the safety of people in the sex trade after this crackdown, DiAngelo founded the Sacramento branch of the Sex Workers Outreach Project. When SESTA-FOSTA was signed by President Trump in April last year, she braced herself for a similar fallout.

“Our streets are what we call ‘lit’”

The year SESTA-FOSTA went into effect, San Francisco police say reports of sex trafficking spiked by 170%, though the reasons aren’t altogether clear. Police say reports are up because of increased outreach, but others aren’t so sure. Anecdotally, DiAngelo and other sex worker advocates around the country say many have been forced to work on the streets after Backpage shut down.

“Our streets are what we call ‘lit,’” DiAngelo says. “People are in trouble. I mean, our hotline here–we do not have the resources to touch the calls we’re getting now.”

The Sex Workers Outreach Project has a hotline for sex workers and others to call when they’re in trouble. DiAngelo says she received calls from women who are suicidal because they’ve been forced to work on the streets and return to dangerous pimps. She says women have called to say they’ve been robbed and assaulted in the aftermath of SESTA-FOSTA. Others, DiAngelo says, have made up for lost income by negotiating higher prices for not using condoms.

“When we talk to the workers about, like, ‘This isn’t safe, you could die nowadays,’ we could get comments like, ‘You’re kidding, right? I need to eat. I won’t live long enough to care about that if I can’t eat,’” DiAngelo says.

The state of online sex ads

Data showing the impact of SESTA-FOSTA is only beginning to come in. A Washington Post analysis shows that the volume of worldwide sex ads plunged 82 percent from March of last year to mid-April.

But that same analysis shows that since then, the volume of ads has since been on the rise. Reddit, Craigslist, and Skype changed the terms of their service to ban sex workers. But there are new forums for sex workers like Switter, which operates from countries where sex work is legal.

A report shared with Reuters by Childsafe.AI offers a glimpse into the impact of the law. According to Childsafe.AI, ads are up, but there are less buyers looking to purchase sex.

A complicated issue

“I’m not so naive to think that turning down sites is eliminating human trafficking,” says Vanessa Russell, the founder of the anti-trafficking advocacy group Love Never Fails.

Russell believes SESTA-FOSTA is an important first step, sending a message that, “we’ll no longer just go after the street thugs and exploiters, but we’re going to go after the white collar exploiters that are empowering them.”

A former sex worker, who asked to be identified as Shay C, also supports SESTA-FOSTA. She entered the sex industry when she was around 18 years old, and says advertising online can still be dangerous. "You can screen your clients all you want, but you are still in a vulnerable situation. You don't know what's going to happen to you,” Shay C says.

Both supporters of SESTA-FOSTA and opponents want to see more holistic solutions, like more programs and shelters for those who want out of the sex trade. SESTA-FOSTA may have passed with overwhelming support from lawmakers, but it remains extremely divisive. The continued concerns show that addressing the factors that drive people into the sex industry is more complicated than any one law or website.