Just before 10, on a brisk Sunday morning in November, I arrive at Tilden’s Education Center and find Trent Pearce in full ranger mode: he’s dressed in his khaki uniform, lighting a fire.

As he kneels by the fireplace, Pearce complains, “I’m using way too much paper. My grandfather would turn over in his grave if he saw this fire.” But it gets the job done. Families come into a crackling fire, hot coffee, and…

“I’m hungry,” announces a child.

Pearce responds, “Well, friend, we have cookies available for free if you would like one.”

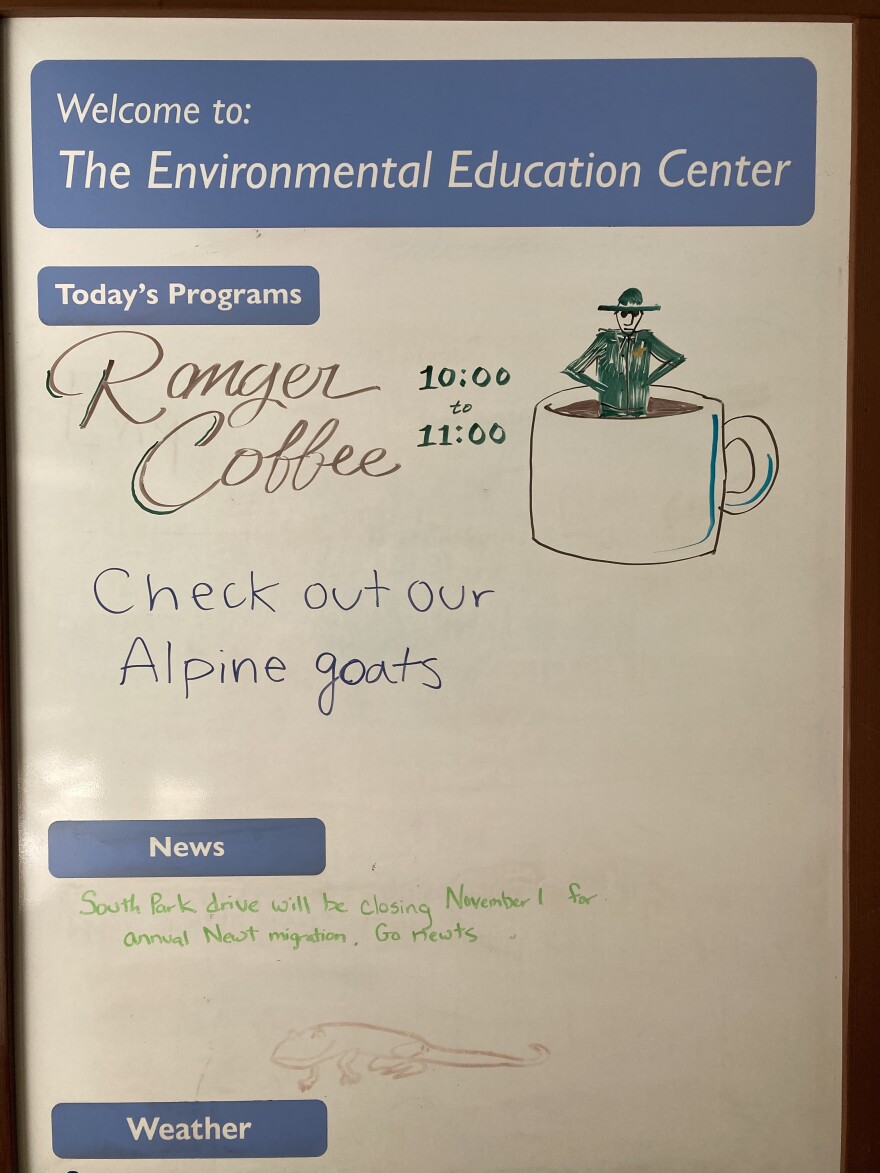

This is Ranger Coffee Hour, a mixer Pearce puts on to mingle with the public:

One woman with a child asks Pearce, “Are you a ranger?”

“I am,” Pearce responds.

Delighted, the woman turns to her child and begins, “Ask Uncle Ranger…”

But Pearce has to add, “Hence the costume.”

Pearce doesn’t enforce laws or deal with maintenance. He’s a naturalist. He interacts with the park’s guests and helps them enjoy the outdoors.

Pearce tries to engage with another young guest by asking, “To where are you hiking?”

The child replies, “No idea.”

“What?” Pearce follows up. “Who’s in charge?”

But the child sticks to his story, repeating, “No idea.”

An exasperated Pearce exclaims, “Oh, my gosh” in defeat.

But he continues circulating. Later, an adult visitor asks Pearce if turtles hibernate. He corrects her, saying “We don’t say hibernating for reptiles for whatever reason. We say brumation and estivation.” He goes on to explain that estivation is for when it’s hot and dry, and brumation is for when it’s cold. On this late November day, it’s cold and dry, so Pearce can’t decide which state the turtles are in currently. He’s full of knowledge like that, and he loves to share it — which is good, because teaching’s a big part of his job as a naturalist.

After Ranger Coffee Hour, Pearce offers to take me on a walk through the woods. He’s got plenty of experience out here. He confirms, “I spend every day doing this — walking around in parks.”

And he’s quick to break out more fun facts. Like when he spots an acorn woodpecker, he tells me, “The acorn woodpecker is where the famous cartoon character Woody Woodpecker… His voice was based on the acorn woodpecker. The laughing.”

Obviously, we take the opportunity to compare our impressions of Woody the Woodpecker’s laugh.

I ask Pearce, “Do you really like working as an educator?”

With no hesitation, he responds, “I love it.” Education is in Pearce’s blood. He tells me, “My mother was a classroom teacher for 31 years.” Then, remembering the mic, he addresses his mom, “If you’re listening, Mom, I hope I got that right.”

But even though his mother was a classroom teacher, Pearce was never one for the indoors. He started out as a wilderness guide. Then he taught elementary school kids at an outdoor school near Big Basin State Park. He wasn’t cooped up inside, but he still felt like he was making a difference.

Reflecting on his time as an educator, Pearce says, “At the end of the day if I got one kid interested in a banana slug and that kid goes and is like ‘Wow! Wildlife is important.’ Then maybe that’s doing something, too.”

Pearce loved working at the outdoor school, but about a decade ago, he decided to become a naturalist. He still teaches, but he has more freedom to just be out here, in nature, where he feels most at home. He tells me, “The people that I talked to at last weekend’s concert, I couldn’t tell you that. But I can still tell you where the first California chanterelle was.”

It’s my job to ask, “Where?”

But Pearce is a little protective. Laughing, he responds, “Well, I theoretically could tell you, but I don’t want to blow up my spot.” He takes a beat, and then he relents, saying the spot was “just outside of Big Basin” near his old outdoor school.

As Pearce thinks about Big Basin and his old outdoor school, his mood darkens. He remembers that are “is all burned and gone now … That whole part of California kind of got erased like an Etch-A-Sketch” by the CZU fire in 2020. That loss was emotional for Pearce. He says, “I went back to my outdoor school, and I almost couldn’t bear to see what I saw.”

California’s fire season has been worse lately — partially because of climate change. Higher temperatures and a prolonged drought have left the land drier, and Pearce and I can see proof of that. We’ve walked to Jewel Lake, an old reservoir. But a lot of the time, it’s more like Jewel Meadow without a drop of water to be seen. We get off the trail and stand in it.

Pearce reflects on the effects of climate change and his role as an environmental educator. He says, “A struggle that I have as an interpretive naturalist who is down here almost every day and talking to members of the public is helping them to accept that … it’s never going to be a big, beautiful lake again.” Winter rains may fill it for a time, but it’ll be dry again next fall.

Pearce continues, “And so, it’s a difficult sell, asking people to let go of this thing that they loved and cherished. And I think that’s what, really, a lot of humanity is struggling with right now. As our planet changes as a direct result of the actions that we have had on our atmosphere, we’re losing these places that we really loved. And we all have to accept that it’s changing, and it’s never going to be the way that it was.”

I can tell this all weighs heavily on Pearce. So, I remind him that change isn’t just an end. It’s also a beginning.

Willing himself back to positivity, Pearce responds, “There will be something new. Thanks for bringing it back to a positive note.” There are a couple of options for the future of Jewel Lake, but Pearce thinks the most realistic involves dam removal and stream restoration.

If that plan goes through, Pearce speculates, “You may come back here in 10 years … and the dam will be gone, and we’ll have an actual stream that salmon can run.” It sounds lovely to me. But I didn’t grow up with Jewel Lake, and it’s not so hard for me to let it go.

We start walking. Ahead the trail is steeper, and logs in the dirt form a series of stairs. At the base of the first flight, we see an aluminum walker, and up ahead we see two women with a dog.

Pearce greets the women, “Hi, how’s it going?”

One responds, “It’s going OK.”

“All right, great,” Pearce says. But he presses, “Y’all are on an adventurous trail with your wheeled device. Everything going OK?”

The first woman says, “Yeah.”

But the other woman, the one’s walker is at the base of the steps, is less sure. She says, “Well, I don’t know.”

The first woman concedes, “It’s a challenge.”

Pearce asks, “Are you going this way or that way?”

The woman with the walker, who identifies herself as Cynthia Papermaster, is unsure, but she says, “Well, we’re hoping to go that way, but…”

Pearce responds, “OK, well, you’re almost finished. You got one more major obstacle, and it’s just a narrow spot where the trail goes between two trees.” He asks if there’s anything he can do to help them.

Only half-serious, Papermaster says, “I need help with the walker.”

Without missing a beat, Pearce asks, “Do you want me to carry it up for you?”

Papermaster lets out an incredulous, “What?”

Before she’s even done with her exclamation, Pearce is walking back to get her walker. He says, “I am a park ranger. I can help.” He might have second thoughts when he actually picks up the walker because he says, with a hint of surprise, “Oh, this thing is heavy.” But Pearce carries it anyway.

Papermaster can’t quite keep up, but she walks capably with her dog and her friend. Before long we make it to that obstacle Pearce mentioned, and the teacher in him comes out. He tells us, “This is one of my favorite spots in the whole nature area. This is one gigantic bay laurel tree … When you walk through the path right here, you’ll see it’s connected in the middle of the trail.”

On the other side, Pearce sets the walker down and tells Papermaster, “OK, I’m gonna let you drive from here. It’s flat and graded for the rest of the way out to the parking lot.”

With gratitude, Papermaster says, “So, Trent, I’m gonna send a note to your employer. Not that you need any further recommendations, I know. I just want to pay a compliment.”

It was just too perfect a moment. Being a reporter, I had to ask, “That was great. Did you plant that for the interview?”

He plays along, jokingly saying, “Yeah, I planted that.”

But of course he didn’t. That was just Trent Pearce doing his job as a park ranger and a naturalist — enjoying time in the great outdoors and helping others to do the same.