Last week, there was a new development in a years-long debate about what to do with a controversial mural at San Francisco's public high school George Washington High. The board is required to leave it as is, after a California Superior Court ruled that they failed to follow environmental impact regulations.

Here’s what the mural looks like: there’s a bucolic green setting in the background. In the foreground, George Washington is pointing west. A cohort of pioneers, painted in black and white, are walking over the dead body of a Native American. It’s not unlike a Diego Rivera Mural; in fact, it was painted by his student, Victor Arnautoff, in 1936.

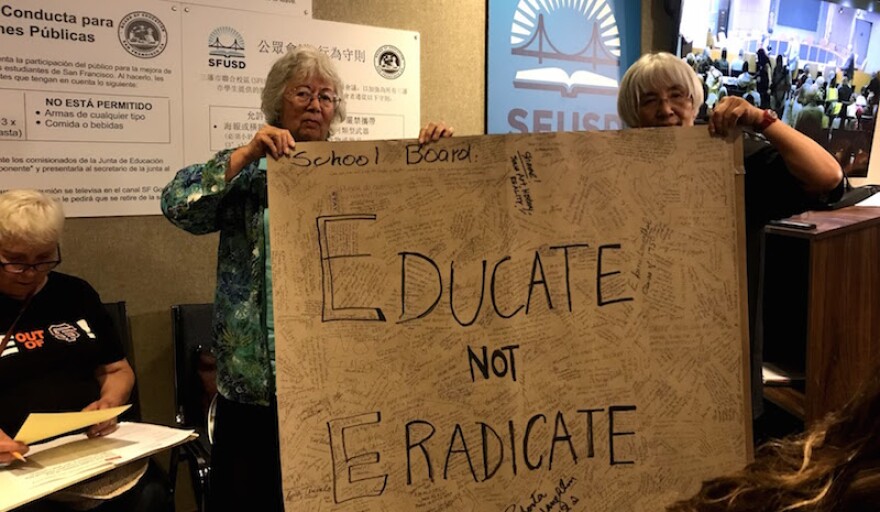

And more than 80 years later, officials decided to let the public in to George Washington High School to see the murals for themselves. The hallway is packed. Some are protesting the murals’ destruction.

Bob Sanchez, who graduated from George Washington in 1966 says, “Even if they covered it and brought it out for educational purposes that’s one thing. But destroy them I think is just wrong.”

But not everyone here wants to save the murals. Amy Anderson is a member of the Objibwe and Ahkaamaymowin of Metís Nations. She’s often the only one in the room voicing indigenous concerns. Her son Kai, an incoming senior at George Washington, did not want to join her.

“I did not push him to come into it because he’s going to be here day in and day out for his senior year starting very soon, so he needs to shore up on his emotional strength to get ready for that,” Anderson says.

Then, she gestures to the mural. “So what you’d think? Of my dead uncle over there.”

I’ll reserve my opinion. But here’s what some others in the rooms have to say:Rico Tacota, a local artist says, “For me, the art is much more magnificent than I expected.”

A woman, who introduced herself as Sasha, says, “It’s brilliant. It’s such a chronicle. It’s so vivacious and important it’s just a beautiful, tastefully done record. I don’t see blood, I don’t see anything offensive around here at all.”

And there’s one person here with a unique connection to the artwork: Paul Arnautoff is the great-grandson of the artist. He says that his great-grandfather was a social realist. “His personality and his values came through his artworkand he believed in depicting history and the people as accurately as possible and to help raise up the stories of people that were not being told, and ignored.”

WHO WAS VICTOR ARNAUTOFF?

Robert Cherney is a retired professor of History at San Francisco State. We meet him at the chapel in the Presidio to look at one of his favorite Arnautoff murals.

Cherney wrote the only Arnautoff biography, and he says Arnautoff was painting Native history when nobody else was. “Unlike many artists who were depicting history in the 1930s he did not begin with the arrival of Europeans. Instead he began his depiction of history with the Native Americans who lived in this area,” he says.

Arnautoff was radical in his day for including indigenous people at all.

Victor Arnautoff was born in 1896 in Imperial Russia. He fought in World War II, and then in the Russian Revolution... for the losing side. Cherney says, “All that time he had wanted to be an artist and all the military service had simply delayed his goal.”

Arnautoff escaped as a refugee to China and ended up training soldiers for a local warlord to make money. Lucky for him, he ended up marrying into a wealthy Russian family, which also fled after the revolution. In fact, his father-in-law paid for Arnautoff to come to America and go to art school at what became the San Francisco Art Institute.

But his student visa ran out in 1929 and he had to leave the country. His advisor, the famous artist Ralph Stackpole, said, Hey, if you can’t study in America anymore, go to Mexico. I’ll hook you up with my buddy, Diego Rivera.

Arnautoff went to Rivera and said he would like to study with him and Rivera said: I’m not taking students but I’ll hire you as an assistant. “You will learn every step of the process of making frescoes, from hauling water up to applying the final paint,” says Cherney.

For two years, Arnautoff studied with Rivera. And throughout the long workdays, they talked politics. Riverra had been in and out of the communist party in Mexico. By the time A and his family arrived there in 1929, he was out. He had been expelled for “bourgeois tendencies.”

Remember, Arnautoff fought against the communists when he was a soldier. But Rivera’s worldview led Aurnatoff to rethink socialism.

After his apprenticeship ended, Arnautoff went back to San Francisco to pursue a career as a muralist. By then, the Great Depression was in full swing.

Unemployment was rampant. But once again, Arnautoff was lucky. Franklin Roosevelt founded the Works Progress Administration. And as one part of that, he created the Public Works of Art Project to provide employment for unemployed artists. “This had never been done before,” Cherney says with a chuckle.

The working class was the subject matter for Arnautoff’s famous mural at Coit Tower. Everyday workers were also featured in his mural over in the east bay at the Richmond Post Office.

But during renovations for the Post Office in the 1970s, the mural, “Richmond Industrial City,” was detached from the wall, rolled up, and stored in the basement. It was considered lost for decades. That is, until someone came along for the rescue.

DISCOVERED IN A BASEMENT

Melinda McCrary is the executive director of the Richmond Museum of History. She shows us the mural wrapped up in a huge plastic tube in the museum’s basement. “When I first saw the mural, I started to cry,” she admits.

McCrary first heard about the mural in 2013. She sat down with a longtime member of the museum. “He lives in Marin and he said, Melinda do you know that there is this mural that's lost. And I said no. And I learned more about it and I thought I'm going to find this thing.”

And digging up stuff is kind of her thing; she’s an archeologist.

Her search led to a janitor at the Richmond Post Office, who sent her a tip about a mysterious box sitting in the basement. “The janitor sent me a photograph of a label and he said I found this crate in a closet that hasn't been lit for a really long time,” she retells.

It was the missing Arnautoff mural! But she couldn't just go over there and grab it. It took another two years negotiating a loan agreement and planning the logistics of moving a 13-foot mural. Then, disaster struck.

McCrary read a news story that there was a flood in the Richmond Post Office. “I know my mural that I've negotiated two years is down there like in the water right now.

So she went to investigate the damage. “But the conservator put the mural on stilts. So it was on stilts that like eight you know eight or ten inches. So it was just inches from this disgusting water of nasty, but it didn't get wet at all.”

Since the mural is still rolled up, McCrary shows us a picture of it. It depicts an array of working class individuals set against an industrial backdrop of Richmond’s port and oil refineries. “The other group of individuals are obviously longshoremen and we know that because they wear white hats. One of the gentlemen is wearing a union pin which is absolutely exciting.”

Back in the 1930s, the International Longshoreman’s union was one of the first to racially integrate. Cherney says the inclusion of a black longshoreman was Arnautoff’s way of supporting one of the most progressive unions in the world.

But the depiction of an empowered black man is in stark contrast to the images of slavery and a dead Native American in a school hallway.

ARNAUTOFF CLASHES WITH BLACK POWER

Students have been demanding the mural’s destruction as far back as the black power movement of the 1960s.

“The [SFUSD school] board and the [San Francisco] Art Commission really wanted to save those murals in those days. And the students were having none of it,” says Dewey Crumpler, a professor at the San Francisco Art Institute. He was an up and coming artist when the school board reached out to him in the late 1960s, And what did Crumpler suggest? Paint more murals!

“I had hundreds of discussions with these students and the faculty for years. I suggested and they agreed and the black panthers who were at the forefront of this movement said that the mural should be about people of color.” But the school board backed down. Crumpler says, “the art commission rejected the notion of essentially a just-out-of-school student would make murals in an institution that had some of the most important murals in San Francisco history in them.”

So high school students took matters into their own hands. They threw ink on the Arnautoff mural in an act of protest. “If the board of education or any of the art commission didn’t have to address that they never would have addressed it,” says Crumpler.

But the school board finally caved and agreed to fund the response murals.

Like Arnautoff, Crumpler also went to Mexico to learn about mural painting.

In Mexico, he was introduced to Diego Rivera’s successors: Pablo O’Higgins and David Alfaro Siqueiros. “They were first of all powerful, they were energetic. They pay attention to the space, the architecture, not just the walls.”

Crumpler came back to George Washington High, and started painting his own fresco murals depicting Native revolutionary heroes, black power, and asian american culture. “As you came through those doors, you were confronted with a fully alive archetype of the power of Native American culture and resilience, whereas the other Native American is dead,” notes Crumpler.

Even though Crumpler started the response murals, students still wanted the Arnautoff mural gone. Crumpler disagreed. He explained his thinking at a packed school board meeting.

“But if you want me to paint the mural,” he told them, “I can’t paint the mural if I’m going or you’re going to destroy this other mural.”

Crumpler spent a lot of time with Arnautoff’s murals. And he was inspired by their message.

“He is really trying to show us the problematic, really critiquing this notion that this George Washington was a liberator. He liberated white people, he didn’t liberate black people. The truth of history [is] that Washington was both an extraordinary visionary, all the founding fathers were, but they were psychostic on race. And that was my argument and I think that was Mr. Arnautoff’s argument. And that’s why I said that if you destroy his murals … my murals were designed to live on their own. But they don’t live on their own historically. They punctuate and make even more important the dialogue that they’re having with Arnautoff’s murals.”

THE MURALS ARE SAVED, BUT AT WHAT COST?

Back at George Washington High School, Crumpler’s murals are taken down for Summer construction. William Gi is a student and he’s here at the viewing with his dad. He says a lot of students are apathetic about the Arnautoff murals’ fate.

Adults are much less so.

“Is San Francisco really the snowflake capital of the western hemisphere?” asks Robert Flynn Johnson, who was a curator at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. “The Taliban they were upset by the Buddas what did they do they Blew it up? Hitler didn’t like books, he burned those up! Does Sf really want to be on the list with the taliban and the Nazis? Some people do!”

Amy Anderson, the indigenous parent you heard from earlier, hears stuff like this all the time. She’s often been called a book-burning Nazi. “But that doesn’t make any sense at all because the entire message we’re trying to get across is that this is for the students,” she says.

When her son first started going to George Washington High School, he kept his head down when he passed the murals. “When a kid walks into a school building you want them to feel like, Hey, keep your chin up. You can do this. It really affected me when he told me he doesn’t even look up at the murals anymore... because it’s painful, it’s hard. That could be our uncle, laying facedown...on the ground. Shirtless. Dead. Lifeless. That’s painful.”

The image of a dead Native American also reinforces the stereotype that all Native people are dead, or trapped in the past. “But to see it in a school hallway?”

Anderson says teaching the history of slavery and genocide belongs in an intimate setting, like a classroom. And when people say Arnautoff was just “portraying history, as it was …” Anderson insists, “It’s telling our story from that settler-colonial perspective. And it does hurt. I know what my story is and that’s not it.”

You can never erase that harm from history, even with paint.

But whitewashing history never was the desire of people like Anderson, who want the murals painted over. It was about prioritizing the feelings of students of color.

Rick Prelinger is outside the mural viewing, taking it all in. He’s a professor at UC Santa Cruz and creator of the Prelinger archives. He thinks the support for saving the murals is coming from the wrong place. “It’s really disappointing how generaltionalized the group here is. That it’s mostly white lefties of a certain age like me who are just coming to terms with how emerging people are feeling about this. I just wish people were concerned with how students of color felt some years back.”

On August 13, the school board reversed its decision to paint over the murals. But it wasn’t motivated by a change of heart. Faauuga Moliga a school board member, said this before the final 4-3 vote: “We got school next week! how long is this gonna go? But this can not continue — I don’t wanna fight with you people. I’m not. We have kids, and I have staff and a district to support. And so as much as it breaks my heart to go the route that It’s my journey and my feelings and I have to deal with it.”

The board voted to cover the murals behind wooden panels.

So preservationists can rest easy that the murals are safe.

But that’s what everyone thought 30 years ago. The school board already covered the mural in the 1970s. And some old wounds just won’t heal. Amy Anderson isn’t giving up.

“Once I feel like I’m ready, just pick back up and start organizing again to figure out how we’re going to get that paint up there,” she says, tears rising. “it’s been hard work. And it’s been worth it because it’s for our students, it’s for our kids, it’s for future generations that we want to see the white walls.”