Starting a small business in the Bay Area can be quite a chore. To be successful, you have to twist yourself into unusual shapes.

To find a real-life example of that, look no further than Stanley Roth. You can usually find him outside of Macy’s in San Francisco’s Union Square, selling hot dogs to hungry shoppers and tourists. Stanley’s cart, Stanley’s Steamers, became the first legal food cart in San Francisco in 1975.

How Stanley started that business is an odyssey told in red tape and government documents. It began with a simple premise: long before food trucks and pop-up shops hit San Francisco’s streets, he was looking for a summer job to pay his way through law school at UC Berkeley.

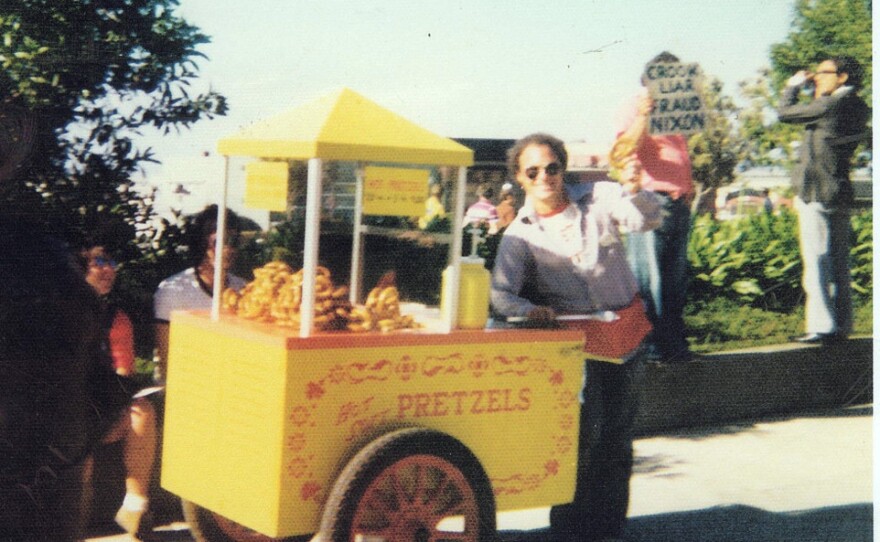

While having a pretzel at a cart on campus, Stanley decided to get into the business.

“I bought some pretzels from the cart and I took them to San Francisco, and I sold out in an hour,” Stanley recalls, “and I thought, this is a good way to spend a summer making money and paying for school.”

It was much better than his gig at the time, anyway – making $3.83 an hour working for Hertz. But unlike most summer jobs, washing windows or painting houses, Stanley needed the city’s help to get started. So he went to the first agency he could think of: the police department.

“They sent me a piece of paper that said, ‘Come down with two passport photos and $8.50, and you get your peddler permit,’” says Stanley.

Piece of cake, right? Not so. When he got there, officers told him that because he planned to use a cart, he’d have to get a sidewalk occupancy permit. Stanley quickly found himself caught in a bureaucratic pretzel.

The journey begins

“When I went down to get the sidewalk occupancy permit they said, ‘No. We don’t issue that permit. You have to go back to the police department,’” he remembers. “So I went back to the police department and they said, ‘Well, without that permit we can’t accept your application.’ So I went to the board of permit appeals, and I said, ‘I’d like to appeal this,’ and they said, ‘Do you have a denial?’”

Stanley did not. As it turned out, though, voters were considering a street artist ordinance that might straighten out the process. It did, in fact, pass in June of 1974. So he returned to the police department, only to find that the law hadn’t changed a thing. Frustrated, Stanley resorted to wit.

“I said, ‘Give me a Street Artist license.’ And they said, ‘For what?’ And I said, ‘Baked sculptures of flour and water.’ And that’s how I started selling pretzels,” he says.

Remember, there were no food vendors or street artists in San Francisco at the time, and most were fearful of disrupting the status quo. As a result, he says, the city wouldn’t get off his case.

On his first day on the job, a San Francisco health inspector approached him to ask for a health permit. Stanley didn’t have one. The inspector explained that the pretzels had to be wrapped, and the cart had to have handwash facilities. He set up a meeting for Stanley to come in to talk with city officials and figure out what to do.

The turning point

A couple of nights nights later, Stanley accompanied his roommate to the pet store to get medication for his sick fish. There, he had a fateful encounter that changed everything. The pet shop owner prescribed tetracycline, a prescription drug, for the fish.

“I asked the pharmacist, ‘How are you prescribing tetracycline for fish when that’s a controlled substance?’” he says.

The pharmacist pointed to a sign that read “the pharmaceuticals we sell are for pet use only and are not intended for human consumption.” Under it, there was a citation from the California Health Code.

Stanley took a quick trip to the library to look up the law.

“It said that if you’re selling something people might mistake as food but you don’t want to be considered food,” he recalls, “you have to post in three inch high red letters that your food is not for human consumption.”

The next day, Stanley posted that message on his cart.

He says, “I had my cart out on the street, and I had two pretzels hanging from fishing line that said, ‘Two pretzel earrings: $25 each. Or make your own: $0.25 each. The pretzels I sell are delicious are not intended for human consumption.’”

A gray-haired gentleman came up and bought a pretzel and asked what the sign was about.

“I told him the whole story, and he said, ‘Thank you. Read my column next week.’”

The man was Herb Caen, the legendary San Francisco Chronicle columnist considered by many to be the voice of the city. After the article surfaced, Stanley’s story went viral.

The city bends … but doesn’t break

The city granted him another meeting and offered to make his street artist license good for food, as long as he got a health permit. That, however, didn’t prove easy, either.

“I had to have hot and cold running water, I had to have a three-compartment utensil sink, I had to stand inside of the cart, it had to have four walls, a ceiling and a floor. But the police code made that cart be no bigger than a card table,” he says, “so I was basically out of business.”

Stanley was angry. But he wasn’t ready to give up. The city gave him an alternative: if he wrapped his pretzels like candy bars, they’d give him a pass. He couldn’t do that, since he wanted to serve the pretzels hot.

One day, while walking down the bread aisle at Safeway, an idea came to him.

“I started looking at the French Bread, and I thought, ‘That’s not wrapped like a candy bar. That’s open on one end. And how is that possible?’” he says. “I mean, I could touch it, I could lick it, I could do anything I wanted to it, and somebody would buy it.’”

Stanley called up the president of a local bread company who told him that their products were not classified under the California Restaurant Act, but were considered “hard-crusted, hearth-baked rolls” under the Bakery Sanitation Act of 1927.

“I said, ‘How do I do that?’” recalls Stanley. “He said, ‘I have no idea, but call the health department.’”

By then, Stanley had become persona non grata at the San Francisco Health Department, so he reached out to state officials who told him that a group called the California Conference of Directors of Environmental Health, comprised of dozens of officials from around the state, could rule on his case.

Stanley got on the agenda and took a trip up to Sacramento. The Conference of Directors saw things his way.

“So I walked out with a piece of paper saying that pretzels were hard-crusted, hearth baked rolls, and my carts were now considered bakery delivery vehicles and were considered legal if enclosed on three sides like a french bread wrapper,” he says.

But that’s not all.

Stanley thought he’d scored a major victory. But when he got back to San Francisco, the police department called him to a hearing and promptly revoked his street artist license on the orders of the city attorney.

“So I go to the Board of Permit appeals with my case,” he says, “this whole story, and the fact that my street artist license has been revoked by the police department.”

Just to recap, Stanley Roth had already been to the police department, and the Department of Public Works, and the police department, again, and the Board of Permit Appeals, and the police department, again, and the health department, and the pet store, (and Safeway), and the California Conference of Directors of Environmental Health, and the police department, again.

Finally, on December 3, 1974, “the Board of Permit Appeals ruled that in San Francisco, pretzels are sculptures,” Stanley remembers. “That was a landmark decision on the Board of Permit Appeals.”

That ruling – that pretzels are sculptures – is still on the books in San Francisco.

This story originally aired January of 2015.