We hear a lot about bad air quality in California. And, it’s hard to know what to do about it. But thanks to a 2017 law, two Bay Area communities known for their air pollution are helping set their own air quality policies. But what does putting air pollution in the hands of the people really look like?

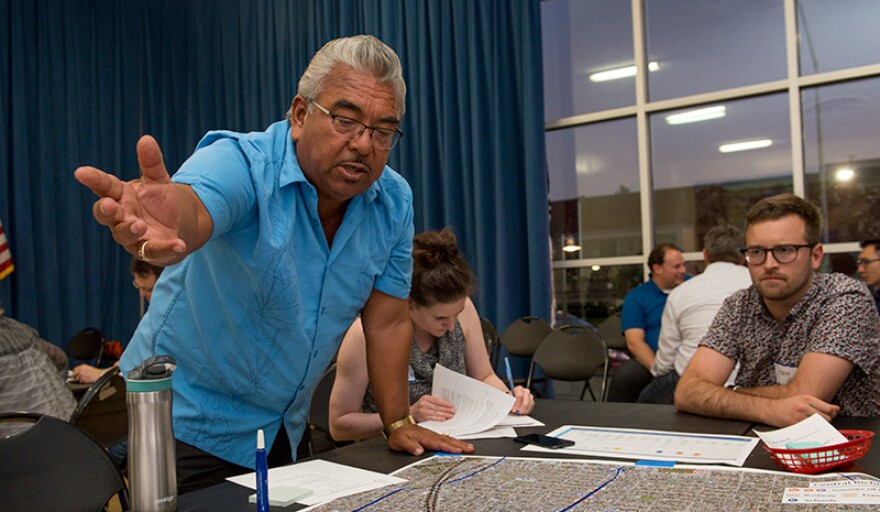

On a Wednesday night in September, the Richmond Civic Center auditorium is packed. Thirty-two people crowd around tables in the center of the room. Doctors sit next NAACP members who sit next to oil industry representatives. This is the Richmond Air Quality Steering Committee, and they’re meeting tonight to make an important decision.

Lawrence Holliday, a 61-year-old basketball coach, joins other community members lining the walls to watch. He’s here because he’s sick of driving past the Chevron oil refinery.

"I don't know what's coming out those stacks. I just know is that when I get close to them my eyes start burning."

“I drive for Lyft sometimes, I drive limo sometimes. So that’s when I notice when I come home late at night that’s when they’re kicking out their emissions,” Holliday says. “I don’t know what’s coming out those stacks. I just know is that when I get close to them my eyes start burning.”

The data is clear: Richmond residents breathe bad air. The city is wedged between two refineries and two highways. It has some of the worst air pollution in the country and a lot of its residents have health issues.

“I have respiratory illness, I have congestive heart failure, I’ve got a growth in my back now,” Holliday says. “One of my close friends just had pancreatic cancer surgery, his wife had a double mastectomy, his son can’t breathe, he had to move out of the city.”

Holliday wants solutions. Tonight, for the first time ever, the community gets a chance to provide them.

In 2017, Governor Jerry Brown signed a landmark law: Assembly Bill 617. Under the bill, ten communities with the state’s worst air pollution are helping set new air policies. Working with their local air districts, they will be installing air quality monitors and drafting plans to reduce local emissions.

In the Bay Area, the state selected West Oakland and Richmond. Last month each community took a vote: start regulating emissions now, or spend a year getting more air quality data first?

"Seven decades of bad health outcomes is enough data."

West Oakland’s committee moved straight into regulation. But their project covers a much smaller area than Richmond, and they’ve already collected years of air quality data from over 100 monitors. By contrast, Richmond only has ten monitors.

At Richmond’s vote, committee members are divided. Some say not to rush the process, while others express concerns about the health costs of delay.

“Seven decades of bad health outcomes is enough data,” says Matt Holmes, Executive Director of Groundwork Richmond.

The stakes are high. So what would a year of more data tell Richmond? I venture down into the cold basement of U.C. Berkeley’s Chemistry building to find out.

Professor Ronald Cohen has collected Bay Area air quality data for years. Cohen runs seven of Richmond’s ten air monitors. They measure things like carbon dioxide, greenhouse gases, and particulates.

“All things that contribute to air pollution and poor health,” Cohen says.

Cohen says that more data doesn’t necessarily mean better data. Richmond’s air quality committee wants to install 100 monitors this year. To Cohen, that sounds like months of effort that might produce unreliable results.

“I’d say make ten really good [measurements] instead of 100,” he says.

Cohen, who’s not on the committee, says that installing a dense network of monitors might just tell you what you could learn from a stroll around the neighborhood. For instance, he says, we already know that trucks emit carbon dioxide. So if there’s a truck yard, why do we need to install air monitors around it to find that out?

“We could have instead just had a camera and counted trucks,” Cohen says. “It’s way less expensive than making measurements for a year.”

"Deeper data matters. And delay causes more disease and disability. So we've gotta do both at the same time."

Collecting more data also means waiting to regulate emissions. For some, the health costs of a year’s delay feel personal.

“Every morning I see about ten patients. And a few of them are going to have respiratory conditions,” says committee member Rohan Radhakrisha, a doctor at the West County Health Clinic.

Radhakrishna thinks that the community needs to act urgently as they pursue better air quality data.

“Deeper data matters. And delay causes more disease and disability,” Radhakrishna says, “So we’ve gotta do both at the same time.”

But at the meeting in Richmond, this new air quality committee has to choose one: delay for data, or regulate immediately.

The committee votes and chooses to delay. Reactions are mixed.

“I’m disappointed, but I’m not surprised,” says Andres Soto, Richmond Organizer at Communities for a Better Environment. “But the real problem is Chevron, the real problem is Levin Terminal, the real problem is all of these industrial pollutants. So this is a charade.”

Randy Joseph engagement coordinator at the RYSE Youth Council thinks differently.

“Everyone’s always talking about Chevron, Chevron, Chevron,” he says. “And for example, if you look at San Pablo, San Pablo isn’t near Chevron, and they have the same health issues.”

Outcome aside, many see the vote as a positive reflection of a community-driven process.

“I was delighted at the openness of the discussion,” says Julia Walsh, volunteer at No Coal in Richmond. “There was a willingness to listen to everyone.”

But Lawrence Holliday came to see his community produce results. And he is left wondering whether their decision would change anything for Richmond at all.

“Committees do a lot of talking, but don’t have no resolve, and no solution,” he says. “So I wanted to ask the question: How many people are sick? How many people are ill, and actually affected by this?”

Holliday wants to remind the committee: they have an opportunity to take action for people like him. Will the new data make the delay worth it? The committee will find out next year.