Fifty years ago today, indigenous people began a 19-month occupation of Alcatraz Island to protest broken treaties and reclaim Native American heritage. Last month, Native American tribes celebrated the anniversary early with a canoe trip to the island. They gathered to honor both the history of the earth, and elders who fought to defend their place in it.

Our stories are made to be heard. If you can, please listen.

On Indigenous People's Day, the sun is just beginning to rise, and the moon is still visible and full. More than 200 people — representing dozens of tribes, families, and communities — gather at Aquatic Park on the shores of the San Francisco Bay.

Ed Archie NoiseCat, a Native American artist, helped organize this canoe journey. He grew up by British Columbia’s mountains with his mother’s people, the Canim Lake Band of Shuswap Indians. He says this event a rallying cry for enironmental justice.

“That is where we are all coming from. The waters pulled us together, the waters sustained us, and the waters give us life,” he says.

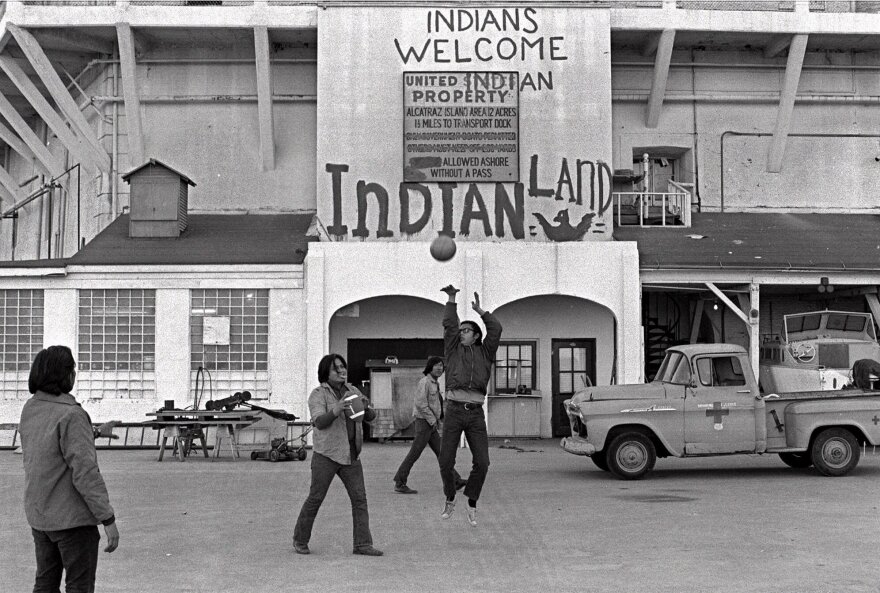

The canoes are also circling around Alcatraz to honor the Indigenous activists who sailed to the island to claim it as their own in 1969. The occupation was meant to bring attention to the government’s mistreatment of American Indians.

“[Alcatraz] is remembered primarily as a site of incarceration, as the place where Al Capone and the Bird Man were locked up,” says Julian Brave NoiseCat, the son of Ed Archie NoiseCat, speaking to a crowd during the celebration. “This Canoe Journey is a way to make sure the history of the occupation, and the Indigenous activists who led it, are remembered.”

“The original idea was that if you came in on New York harbor on the East coast, you would encounter the Statue of Liberty, a symbol of one country’s freedom,” NoiseCat says. “And if you came in on the Golden Gate on the West Coast, you’d encounter Alcatraz, a symbol of Native peoples history, of Native peoples story, of Native peoples rights.”

Kanyon Sayers-Roods is a member of the Indian Canyon Mutsun Band of Costanoan Ohlone People. She also goes by Coyote Woman and describes herself as an ancestor in training.

“I am blessed and lucky to witness the culture resilience of Indigenous peoples, from all around. We are still here,” Sayers-Roods says. “Water is life. When we honor the past, we can shape the future.”

Some of the canoes have grizzly bears carved at the front, because, as Ed Archie NoiseCat explains, the bear is an important symbol of Indigenous survival.

“The last California grizzly was hunted down by the Forty-Niners, captured and then placed in the San Francisco Zoo,” he says. “They were very close to removing the Indigenous people. It’s a very difficult history.”

Many Native American communities in the Pacific Northwest traveled by waterways for thousands of years before centuries of removal, assimilation, and genocide forced some of them out of the water.

Canoe journeys began about 30 years ago as a way for Indigenous people worldwide to reclaim that water culture.

One of the canoes, about 24-feet long and made out of tule reeds and willow poles, departs from the shore. Some of that material was harvested from Mountain Lake in San Francisco's Presidio.

“This watercraft represents the local Native people of the Bay Area, and the People of the Peninsula,” Antonio Moreno explains. “It actually cleans the water by pushing oxygen into it with the wind coming in and swaying the grass.”

“I don’t want to get too much into it, because I get emotional. We’re relying on our Mother Earth, and the mothers that carry us and the water when we were born,” Moreno says.

LaNada WarJack, one of the original occupiers, is grateful to be remembered in this way.

“I’m just thankful that I’m still alive,” WarJack says. “And [with] the plants, the water, the pollution that’s going on, we just need to continue our prayers, because we wouldn’t be here without those prayers.”

WarJack was the first Native American student at U.C Berkeley, and she says the occupation was apart of the larger Indigenous Rights Movement in the Bay Area and around the country.

She was a member of the Third World Liberation Front, who led a student strike in San Francisco State University and then at Berkeley. This action led to the creation of the Ethnic Studies department and Native American Studies.

In the 60s’, Richard Oakes, a leader of the occupation, a San Francisco State student and member of the Mohawk Nation, dove into the water, and swam towards Alcatraz.

“He didn’t make it there that day, because it was cold and a crazy thing to do,” Julian NoiseCat says. “But it ignited a spark.”

On November 20th, 1969, about 80 Indigenous activists sailed to Alcatraz to take over the island. They stayed for nineteen months.

The Indian of All Tribes saidthe Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 gave Indigenous people the right to federal land that wasn’t in use. Alcatraz Island had been abandoned in 1962 when the prison shut down because it was too expensive to maintain.

“Shame on them. It was like, another broken treaty right in front of us in this day and age,” WarJack says. “The government broke every single treaty we had.”

The Coast Guard tried to stop them. The government cut off electrical power when they arrived and blocked access to water, but they had public support.

The Indian of All Tribes sarcastically offered to buy Alcatraz for $24 dollars, glass beads, and red cloth. The occupiers said that was the same price that Indians supposedly received for the Island of Manhattan.

“We will further guide the inhabitants in the proper way of living. We will offer them our religion, our education, our life-ways, in order to help them achieve our level of civilization,” an Alcatraz Proclamation and Letter read, “...and thus raise them and all their white brothers up from their savage and unhappy state.”

The occupation attracted national attention for Indigenous people who had been largely invisible.

“They didn't even know there were Indians left alive, so it kind of took them by surprise that we popped up,” WarJack says.

The occupation was largely peaceful, but it was not without tragedy. One of the main organizer’s 13-year-old stepdaughter died after falling down a stairwell. WarJack says the government kept trying to divide the occupiers, who some of the media portrayed in a negative light.

“They’d say, ‘Well, you’re just young militants.’ And we’d say, ‘We’re young but not militants. And then they’d say, ‘You’re urban, you’re not reservation. And we’d say, ‘That’s where we came from. You're the ones that sent us out here to the city because the government relocation program was supposed to assimilate us into the mainstream of American society.’”

The occupation ended in 1971 when the government forced the last activist off the island. But WarJack says living on Alcatraz forever was never the point. They wanted reparations for broken treaties, and to establish ecology centers, and spaces to teach the history of Native American culture.

“That’s the first thing we wanted to establish was are our identity as Native people, and bring back our culture and our spiritual ways,” WarJack says.

During the occupation, President Richard Nixon ended the government policy of forced assimilation. He returned the sacred Blue Lake in New Mexico to the Taos Pueblo and provided funding for reservation-based health care programs.

“Taking the island ignited everything. Like a rut that hits the water, and it just keeps on going,” WarJack says.

Eloy Martinez was another original occupier. He jokes that he still visits Alcatraz regularly to collect his rent. "Even today, they can't take it. It's still ours,” he says.

The occupation’s message about resilience and community, WarJack says, still flows through Indigenous rights movements today -- from Standing Rock to marches for climate change to canoe journeys around the world in rivers, seas, and in the San Francisco Bay.

“Our fights for treaty rights, our fights against pipelines, our fights to protect children, women, all of that, can be traced in one way or another to that island behind us,” Julian Brave NoiseCat says. “It is our hope that we can reclaim that statement: ‘Alcatraz is not an island, it is an idea.’”

Aftercircling the island, the canoes make their way back to San Francisco. Per Indigenous protocol, the people in the canoes ask for permission to return as they get closer to shore.

“We heard there used to be canoe people down here. We come to share our good medicine,” a representative of one of the canoe families says.

Kanyon Sayers-Roods greets them. “The Ohlone community welcomes you in a good way, we are grateful you had a safe journey and we are happy to share space and share a feast. And welcome to Yelamu,” Sayers-Roods says.

During each canoe journey, Native elders and community leaders are there waiting, and they welcome them back to the land.

"Red Power on Alcatraz: Perspectives 50 Years Later" opens this Saturday, Nov. 23. The exhibit and related events will continue for another nineteen months — the same length as the original occupation.