A leaked document from the Department of Homeland Security proposes to make it more difficult for immigrants who use public services to remain in the United States.

A very cute and very squirmy little girl with pigtails twists in the arms of a man who is trying to hold her and talk on the phone. She wails loudly and coughs.

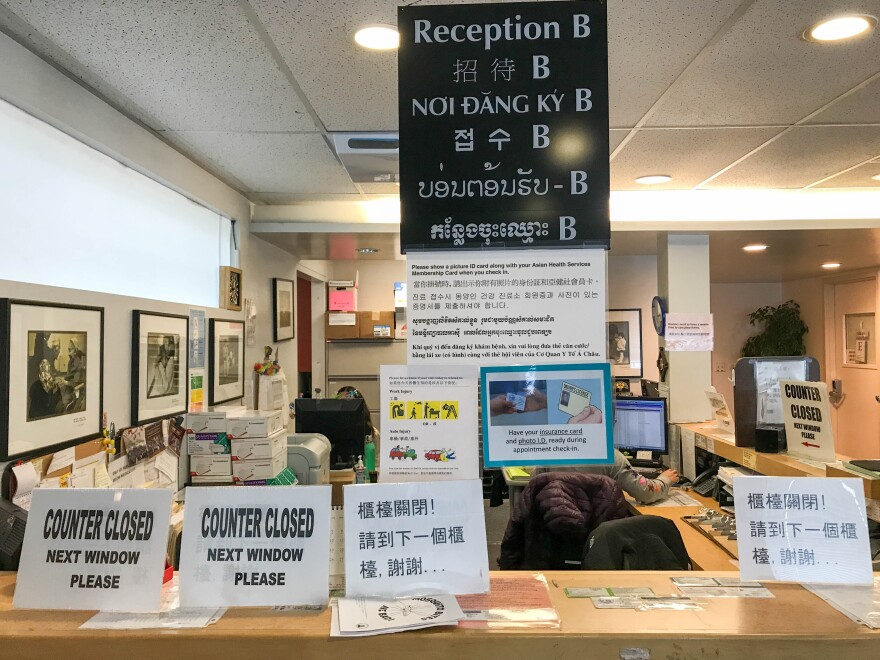

They are in the upstairs waiting room at the Asian Medical Center in downtown Oakland. It’s one of the main clinics run by Asian Health Services. The bulk of their clients are Chinese, but they offer services in 12 Asian languages.

Thu Quach, the head administrator at Asian Health Services, tells me that the organization provides a number of services to primarily low-income clients who are limited English proficient. Many are not citizens of the United States.

“We often are considered the safety net for many of the immigrant population in the local area,” she tells me.

Immigrants make up almost a third of Alameda County’s population, and about 60 percent of that number are people from Asia.

The majority use Medi-Cal or MediCare, or are uninsured. Right now, they can visit this clinic without worrying that it might affect their ability to live in the U.S.

But that all might change because of a government designation a lot of people have probably never heard of: public charge.

A law that’s been around for over 100 years

“Just the term ‘public charge’ is a little bit archaic sounding,” says Sally Kinoshita, the deputy director of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. “It's a term and a concept that has been around for more than 100 years.”

In 1882, as steamships from Asia and Europe brought hopeful migrants to the U.S., Congress passed a number of restrictive immigration laws.

One of them stipulated that U.S. officials should send back to their home countries “idiots, lunatics, convicts, and persons likely to become a public charge.”

By that, Congress meant any immigrant who might need government support — like money or housing — and as such, would become a “charge” of the state.

A version of that law still exists today.

“Public charge is a concept ... under which the government has determined that someone looks likely to be primarily dependent on government assistance,” Sally tells me.

Right now, in 2018, a few groups of immigrants are exempt from being considered a public charge; refugees and asylum applicants, for example.

However certain lawful residents or visa holders who receive cash aid from the government are not exempt. Those programs include receipt of public cash assistance for income maintenance, such as CalWORKS, or institutionalization for long-term care at government expense.

There are a few situations in which people are asked to demonstrate that they won’t become a public charge.

Most commonly, it’s when a person wants to cross the border into the U.S., or when they want to get a permanent-resident card, also known as a green card.

If the official looking at an immigrant’s case decides they are likely to become a public charge, then that is grounds to reject their applications.

When making this decision, immigration officials have to consider you as a whole person, Sally says: “The government has to consider an individual's age, health, financial assets, education and skills … those kinds of things.”

So, the fact that someone uses public benefits, or has in the past, is not enough on its own to make them a public charge.

And the process that adjudicators use to test immigrants — considering many aspects of their life — won’t change.

But, what the government might change is the definition of the term “public charge.”

That is what the Trump administration is proposing, Sally says.

The secret’s out

In the past few months there have been a few draft versions of proposed regulations that have been leaked to the Washington Post and Reuters.

“If implemented, [they] would result in large-scale changes to the way public charge is defined and applied to immigrants,” Sally tells me.

Thu Quach from says the latest leak shows that the administration wants to widely expand what benefits can be considered.

“Going beyond cash assistance and long-term care,” she says, “they want to add things like Medicaid, food stamps, WIC, even subsidies that people receive from the Affordable Care Act.”

In the leaked draft, the Department of Homeland Security claims that previous readings of public charge are too narrow. It quotes Congressional policy asserting that immigrants should be self-sufficient, or rely on their own families or private organizations for help, and should not rely on public assistance.

But, Thu says, people use public assistance to stay healthy, and these changes would likely increase costs for the United States.

“We can be sure that people will not only fall out of coverage, but even when they have coverage, they won’t come in. And as soon as you lose primary care, you'll see the chronic illnesses or the preventable diseases really rise,” Thu warns.

Basically what she’s saying is, if people don’t use public services to stay healthy, it could end up costing more if they end up in the local hospital’s emergency room.

And even though these reported changes are far from becoming law, people are already frightened about what it might mean for them.

A difficult choice

I meet Sophie at the office of Chinese Affirmative Action in the heart of Chinatown, San Francisco. She asked to not share her last name.

Sophie moved here from China almost 3 years ago. She tells me that her life is very full; she works a janitorial job, takes English classes, and raises her two young kids.

“Living here there so many barriers,” Sophie explains, via a translator. “I'm really trying hard to integrate and become a part of where I'm living now.”

The Department of Homeland Security writes in the leaked draft that about 25 percent of immigrants use public benefits, which is about the same rate as the native-born U.S. population.

Sophie tells me, like many immigrants she knows, she wants to get off public services and become more financially stable.

“We're not applying for these benefits our whole lives, we’re just trying to tide over in this transition,” she says. “We have really the ability to you know create a better life for ourselves.”

Sophie uses a number of social services — Medi-Cal, food stamps, WIC, which provides food for babies, and Section 8 vouchers for housing.

None of these currently qualify her to be considered a public charge.

When she found out that the proposed changes included some of the benefits she uses, Sophie says she was scared.

She has her green card, which means it’s unlikely she could be considered a public charge, even if these proposed changes do go through.

But for people who don’t have green cards, it could mean a very difficult choice: give up public services, or risk losing their ability to live here.

Sophie says her fear comes from feeling like a target.

And Thu Quach says she sees that happen a lot: Even when new rules wouldn’t apply to certain immigrants, they’ll still be afraid to go to the clinic for healthcare.

“People are starting to be afraid and oftentimes we say that it's not always just those at risk, but those who may think that if they're an immigrant that they're going to put themselves or their families at risk,” says Thu. “So they'll just decline services or really go into the shadows and not use a lot of this ... we're afraid that even before any changes have been made, people are changing their behavior.”

Like Sophie, Thu tells me that she needed access to public services when she first arrived in the U.S. at age five.

She says her family had nothing when they arrived, and relied on health and food assistance, including the free school lunch program.

She says that help made her who she is today.

“It's my story. It's a story of many of the doctors here and the staff here who have chosen to give back to our nation,” she says. “[W]e're appreciative of what we got, and we've paid back a lot of the public assistance that we were given.”

Thu expects the proposal to modify public charge to be released any day now. And with it, the opening of a public-comment period.

For her, this is personal. Which, is why she’s not waiting around to try to dosomething about it.

Fighting back

Thu is helping build software that would enable people to submit a comment about these proposed regulations to the government, quickly and easily.

She’s hoping that when the time comes, they’ll get at least 100,000 comments, and that the Trump administration will pay attention.